I read for escape, amusement, and information. But for me the greatest value of fiction is the entrance into other lives; the heart of fiction is empathy. Daniel Nayeri’s memoir-novel lets us escape our own world; it amuses and informs. But his chief task is to open the eyes and heart of the reader. “We can know and be known to each other, and then we’re not enemies anymore.”

I read for escape, amusement, and information. But for me the greatest value of fiction is the entrance into other lives; the heart of fiction is empathy. Daniel Nayeri’s memoir-novel lets us escape our own world; it amuses and informs. But his chief task is to open the eyes and heart of the reader. “We can know and be known to each other, and then we’re not enemies anymore.”

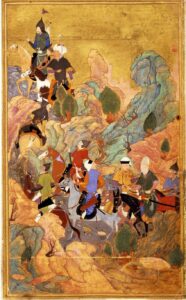

This book is full of riches: suspense, pathos, comedy. It takes me into lives and worlds I never knew: Persian myth and legend, middle-class family life, warm and sensuous, in modern Iran. A death decree when the mother openly converts to Christianity, a year in a surreal Catch 22 waiting for the UN Embassy in Dubai to grant refugee status, grudging support in an Italian refugee camp. And finally a 12-year-old refugee sitting by himself at the back of a class in bleak and hostile Edmond, Oklahoma, where the English teacher gives writing prompts and he tells his stories to sneering seventh-graders.

Persian legends: Destroying the Survivors of Kipchak Corps. source:artincontext.org/persian-art

middle school: image:daily herald

The narrator takes us back and forth and round and round, citing Scheherazade, who told a new tale every night to fend off execution. Though I’m accustomed to an old-fashioned, chronological account, with perhaps a few backwards glances, this is not difficult reading.

The narrator takes us back and forth and round and round, citing Scheherazade, who told a new tale every night to fend off execution. Though I’m accustomed to an old-fashioned, chronological account, with perhaps a few backwards glances, this is not difficult reading.

He tells us stories of many generations as well as his beloved nuclear family, especially his unstoppable mother. Gradually we learn how the 3-year-old watching his grandfather kill a bull in Iran became the 12-year-old in Edmond fleeing a brutal stepfather, but remained optimistic about the future.

His wide-eyed wonder at American ways makes us see them in a new light. There’s his hilarious comparison of American and Iranian bathroom hygiene, when he is finally invited to a friend’s house and tries to figure out how to clean himself. The class trip to a 98-year-old sod house, now a museum. The teacher tells him that in America we cherish historical things, and he thinks of his grandfather’s 600-year-old house ina walled garden lined with mosaic tiles, with a fountain and fruit trees.

sod house museum image:trip advisor

a courtyard garden image:pinterest

An outcast in a foreign land, he cherishes his memories. In an afterword, Nayeri explains that while he changed names, created a few composite characters, and adjusted the timeline, these memories are as truthful as he can make them. “A patchwork text is the shame of a refugee. I am afraid I did not have access to family records, historical documents, or even most of my family members. Perhaps I misunderstood a great deal, in the way that a child misunderstands, but those are the myths I believed at the time. This was my life, as I experienced it, and it is both fiction and nonfiction at the same time. Your memories are too, if you’ll admit it.”

Daniel Nayeri

Nayeri’s memories are moving, sometimes heartbreaking, often comical. I learned so much about ancient Persia and modern Iran and what it is to be a refugee. I fell in love with this twelve-year-old boy.