Aug 16, 2021

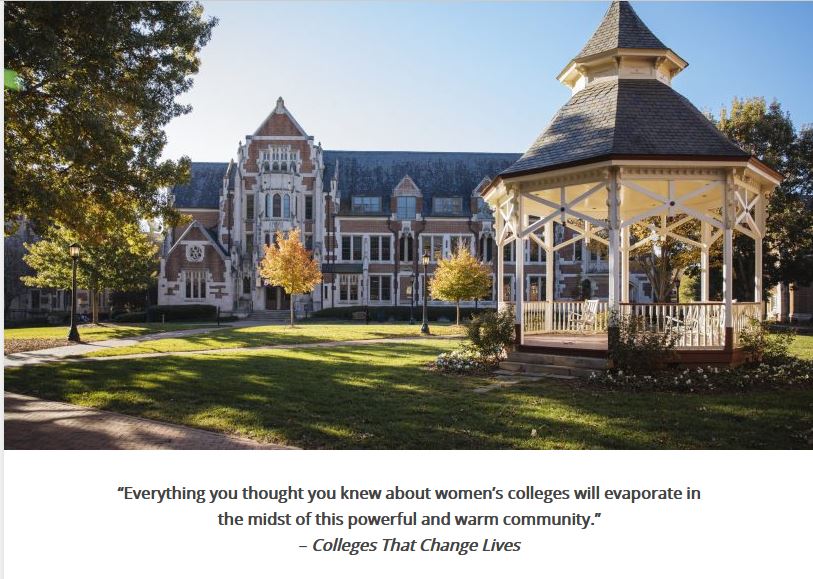

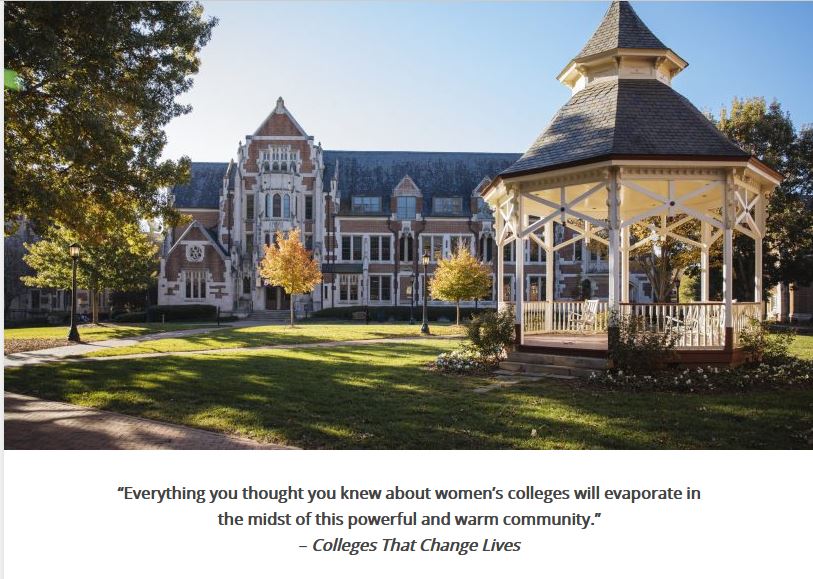

Our granddaughter has lived with us eleven years. Tomorrow we drive to college outside Atlanta with mountains of stuff in two cars. We’ve all weathered tough times and plenty of heartache, but we’ve come out wiser, with our love stronger. She is an extraordinary young woman.

They’re all going to college!

Agnes Scott College

I was finishing a chapter of my novel (I think I am the slowest writer in the world) when I got distracted looking for a version of Bridge Over Troubled Water that I could share with her. I have always thought of this as a song from one friend to another, in the Lean on Me category. But my singing partner and I were working on it last week and came to the third verse, which Paul Simon wrote in the studio because his producer insisted on one more verse: “Sail on silver girl, sail on by, your time has come to shine, all your dreams are on their way, see how they shine… “ I controlled myself as we practiced, but broke down the next morning, when I cried and cried.

Photo by Johannes Plenio from Pexels

I’ve never before suffered from empty nest syndrome. My feelings have always been closer to “Free at last!” But this time, maybe because I’m older and more tender-hearted, maybe because she has overcome so many obstacles, I seem to be heading straight into grief. We will certainly miss her – she is extremely lively and funny, and at dinner I sometimes have trouble eating because we laugh so much.

We lose our children over and over as they grow – the round-headed baby with the huge eyes, the three-year-old exuberantly climbing the monkey bars, the nine-year-old off to the father=daughter dance with Grandpa, wearing the rose corsage he gave her, the eleven year old posing so proudly in her safety patrol belt – they and so many more are long gone, leaving nothing but memories and photographs.

My life will be my own again; I won’t be responsible for anyone but me. My time is my own; I hope I won’t squander it. In the years of raising her I have become a worrier, an anxious woman. (It’s possible I always was, but I don’t think so.) I am quite sure I won’t recover entirely, but based on past experience I’m also sure that there’s a fair amount of ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ When a child is far away most of the daily troubles resolve themselves before we know about them.

Worry makes wrinkles

I began this essay a few days ago. Since I began writing it I’ve been an explosive mix of grief, excitement, worry, pride. Raising children is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

Mar 25, 2021

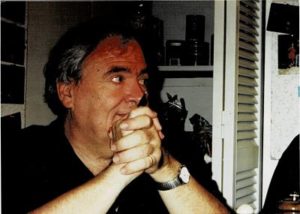

I once wrote that the main thing I fear about aging is the death of more and more friends and family. That was eight years ago, and now at 73 I have reached the time of losses. I have lost a brother, a sister, and seven friends. The experience is as profound and hard as I feared. Each death leaves a hole which no one else can fill, in a shape peculiar to that person, like a missing piece in a jigsaw puzzle. We hear about the deaths of old friends whom we have little contact with, and it sends us back to earlier times in our life. But the people who are part of our present life – whom we talked to daily or weekly – whenever we turn a corner we encounter their absence again.

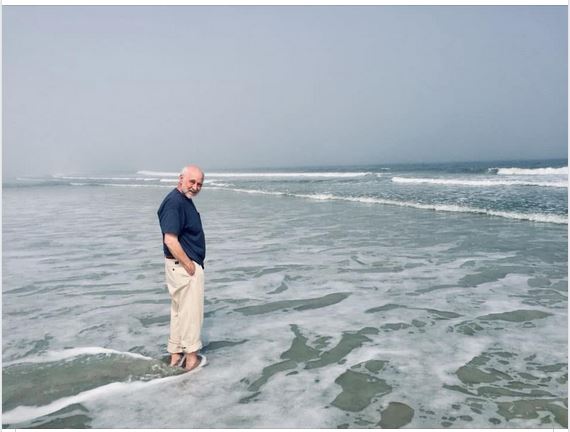

Brother Dickie

Sister Luli

I would like to say I am learning to deal with loss, but I don’t know what that means. The idea that in a year after a death you will have folded up the sorrow and put it in a drawer where you can visit the memories doesn’t ring true.

Grief in a drawer

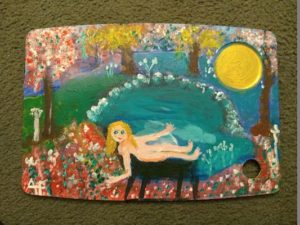

My sister Luli died three and a half years ago, leaving many writings and cartoons. My friend Arupa died a little over a year ago. She was a writer, painter, and founder of the HOME Van; she had asked me to be her literary executor. I carried home cartons and two file drawers with her writings, along with the remainder of her paintings. I plan to compile her writing about homelessness into a book and sell it to benefit homeless services, then share some of her remaining work on Facebook or on this blog. A writer wants to be read.

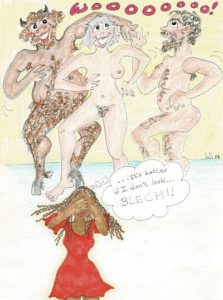

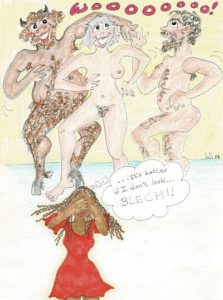

Birthday card by Luli

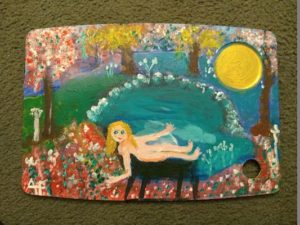

Painting by Arupa

Early in March I finally began reviewing Arupa’s work. Luli’s birthday was March 4, and she haunted the work – when I took a break from Arupa, I would go to Luli’s writing. My friend and my sister had a lot in common (besides their fondness for drawing nudes). Both bore scars from childhood and survived trauma, confusion and pain to become women who were larger than life. They were both writers and visual artists. Luli’s huge, generous heart had a genius for friendship, while Arupa shared her heart and her last twenty years with people who are homeless.

The legacy left by an artist and writer’s death gives us more than memories; we can visit their voice and vision whenever we like. They come back so clearly, with an intimacy and honesty we may only have glimpsed when we were together. But it is a mixed blessing. All that we lost is there before us, right on the page, and we can’t offer comfort, ask questions, share our own stories.

Mourning doesn’t end after a year. As time goes by, grief, at first an acute condition, becomes chronic, flaring up from time to time when we bump into a memory. But I suppose after a few years we become used to the jigsaw gaps, accustomed to grief. Sometimes we deliberately visit the memories; sometimes we run from them. But after someone dies, all we have are memories. If we flee the memories because they carry sorrow, we lose a loved one twice.

Missing pieces

About Arupa: The Fairy Queen

About Luli: Sisters Two

Jun 18, 2020

Bob Freeman died on May 31 at age 79. He was a painter, theater director and producer, gardener, deep thinker, sardonic humorist, dear friend to many, and devoted father to three now-grown children. To me he was the backbone of the HOME Van and, after his wife Arupa died five months ago, also its head and heart, serving the homeless and hungry out of the food pantry in his living room with just a few volunteers to help.

I’ve known Bob eighteen years, but we grew closer after Arupa’s death in December. Working with him on the HOME Van and to prepare for a memorial art show and poetry reading for Arupa, I came to know his generous heart. We were going through boxes of Arupa’s papers when someone came to the door for a food bag. Bob took it to him, and then came back in the room and took his jacket from the closet. “Bob, you can’t give him the jacket off your back.” “Oh, I can get another.”

An Arupa painting

Gia, Ezra, and Peter, Bob’s three children, came to town to arrange the memorial service. Gainesville was on the fringes of tropical storm Cristobal and the heavens were weeping for Bob, so Joe and I set out with umbrellas to the gathering place, an early 20th Century house with porch and turrets. I saw some people I knew and many I didn’t. We gathered six feet apart on the lawn and porch, raising and lowering umbrellas as needed. We signed the guest book, one of Bob’s sketch books that he always carried, filled with pencil and watercolor drawings. A friend played a long mournful tune on her violin. Another read a letter from Anna, Bob’s first wife and mother of the children. All three children spoke – they had an idyllic hippie upbringing with Bob.

A few Jazz Bandits

We walked to the community garden, led by three brass instruments from the Jazz Bandits playing Swing Low, I’ll Fly Away, and many other lively gospel tunes. It rained, it stopped, it rained, it stopped, and then it came full force. We huddled under a couple of carports, still doing a pretty good job of distancing. Bob would have enjoyed our gathering under the No Trespassing signs, and the faint odor of marijuana.

When the rain subsided from torrential to steady, we walked on, past the Matheson Museum and through Sweetwater Park to the community garden. I don’t know how many plots are in the garden, but it’s filled with collards, kale, tomatoes, sunflowers, and exuberant weeds. Next to the plots is a grassy stretch, and there Bob’s children planted two peach trees, with Bob’s and some of Arupa’s ashes (the rest are going to Vermont, Arupa’s native land.) The children talked of their times playing in the garden. I read a poem by Shmal, one of the main HOME Van volunteers, who has moved to Seattle to be with family.

McRorie Community Garden

From the garden we went across the street to hear the Jazz Bandits play at band-members Jackie’s and Mary’s house – they live next door to HOME Van Central. We milled in the street, pretty much social distancing, but lowered our masks to eat Bob’s collards and drink Jameson’s whiskey. (Bob was a whiskey drinker.)

Every day I think of something I want to ask or tell Bob, and then remember I can’t. And Bob’s death means the end of the HOME Van. We all wondered whether there was a way to keep it going, but Bob and Arupa’s house was HOME Van Central, and the project – first the drive-outs and later the food pantry – was full-time unpaid labor.

We started the HOME Van eighteen years ago; it hurts to think of it dying. Guided by Arupa’s vision, we were tiny and improvisational, meeting people where they were, and doing whatever we could to help them, always in a spirit of friendship and a bit of anarchy. I am just at the age where people are beginning to fall around me, and each death punches another hole in my world in the unique shape of someone I love. The loss of the HOME Van does the same, for me and for Gainesville.

The Van

Home Van Centr

Oct 17, 2019

Luli Gray was an adorable and spoiled little girl, a brilliant student who barely made it through high school, a confused and very young bride, a vagabond in Europe, a waitress, file clerk, janitor, aspiring actress, professional cook, and finally in her mid-forties a successful writer. Most important to me, she was my sister. If you are lucky enough to love a sister, you know that the bond is deep and strong. You share memories back to your earliest days, and the giggling girls are still there in old age.

Luli and Me

After Luli died, as I searched through Windows Explorer for pictures, I came across the draft of an essay she wrote in her late fifties. She had heard Susan Farrell, the great ballerina, talking about her life. Farrell had wanted to be a dancer since childhood, and she worked hard and steadily to follow that path. She had no regrets. Luli envied her. She wrote:

I have backed into my life like a bird into a propeller blade, squawking and flapping. Sometimes I have felt torn apart like that bird, thinking I would never fly again, or even survive. And if someone asked me, ‘Do you have any regrets?’ I would say, ‘Yes. Many.’ I do not dwell on them very often, and sometimes I suspect that my disasters as much as my successes have made this odd Mulligan stew of talent, terror, laughter, despair, joy and rage that is me. Sometimes I quite like the stew. But there was no clear path, ever.

Luli was finally making an adequate living as assistant to a food writer, with side gigs as a recipe developer, when she began writing seriously.

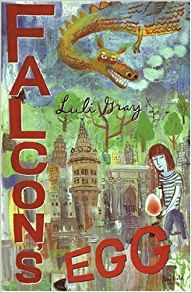

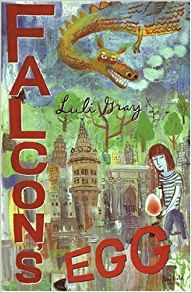

I scribbled short stories and sent them to magazines. Lots of stories. Lots of magazines. Lots of rejections. Apparently, nobody wanted my stories. I kept on writing. I got up at 5AM six days a week so I’d have time to write before leaving for work. I sent out stories; they came back. I sent them out again. One day, after a year of this, a story began to grow. It had a dragon in it, and a child. Could I possibly be writing a children’s book? Yes. Holy cow.

I wrote the first draft at white heat, in less than two weeks. I wrote and rewrote and sent it out to a few agents. Three weeks later I had an agent and a book contract with a major publisher. Finally, after more than forty years, I have found a passion that sustains me, a desire to keep reaching for my unexpected, unattainable star.

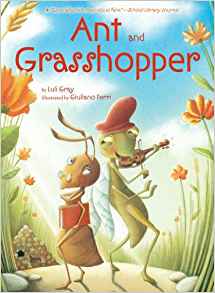

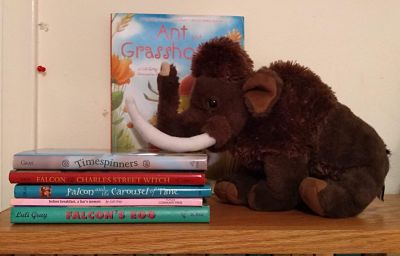

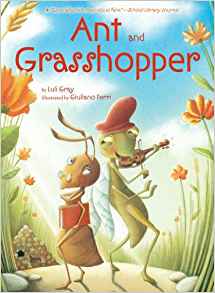

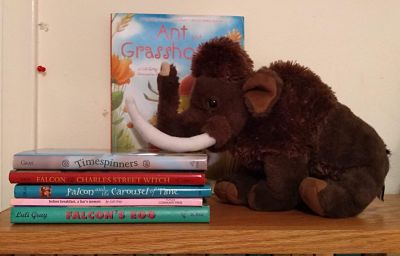

Luli followed the first novel, Falcon’s Egg, with a memoir of our father that she drafted in a 24-hour writing contest, which she won. She returned to Falcon with two more books, and then wrote Timespinners, a book about a brother and sister whirled away to the good old days of Neanderthals and wooly mammoths. An auto-didact who read widely (she re-read Moby Dick, including the whaling sections, every couple of years), Luli was fascinated by Neanderthals. She turned to Aesop, and wrote Ant and Grasshopper, a picture book with beautiful illustrations by Giuliano Ferri. This took years. As any writer knows, telling a story in 750 words is a lot harder than 75,000.

Luli was her own most severe critic. She acknowledged the worth of Falcon’s Egg, a Newbery Notable, but dismissed the rest except for Ant and Grasshopper, her first picture book. It helped that our late brother Richard, a prominent book critic, told her, “This is a perfect book.”

Now we have another book from Luli. I won’t call it the final book, because her agent has two more manuscripts of transformed fables to peddle, and as Luli tells us, there will always be Hope in the world.

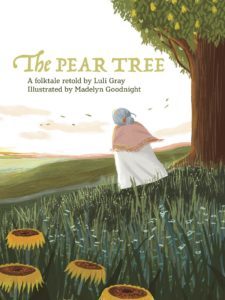

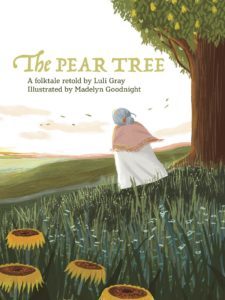

Luli learned the Spanish folk tale of Tia Miseria y La Muerte from Richard’s wife Esther when she lived with them and their seven children in Madrid. She transformed it and made it her own, replacing Miseria (misery) with Esperanza (hope). In Luli’s version, though Death must do his necessary job, there will always be Hope in the world. She worked many years to realize her vision of The Pear Tree, but she couldn’t get it published. A picture book about death? No way.

About nine months after Luli died we heard from her agent: Penny Candy Books wanted to publish The Pear Tree. Crying, I stormed around the house. Why couldn’t this have happened before she died? She wanted it so much, and she would never know. It took a few days, and many emails with her close friends, for me to begin to rejoice.

Luli’s books delight me, but she was not just a writer. Luli was a cook, cartoonist, cat-lover, and above all, generous, loving friend. She had charisma, compounded of eccentricity, humor, and her avid interest in all sorts of subjects – gypsies, lepers, Neanderthals, nuns, books, cats, food, gardens – and especially other people.

Luli’s garden – old shoes are excellent planters

She made friends everywhere and all the time. Some were friendly acquaintances, like the bus drivers with whom she shared gardening stories or the copy store clerk who helped her print her homemade greeting cards. She would meet women at the gym, arrange to meet for coffee, and soon progress to lunches that lasted several hours. And then she had her long-time friends, her New York friend Mary Jane, her neighbor Margaret, Kathryn Hubbell, the group of writers she called the coven, and many others, who came together as Friends of Luli in the hard last year of her life.

Luli and I had the special friendship of sisters. We shared a family history, family culture, jokes and references that only we could understand. We shared love, laughter, and outrage. We visited each other several times a year, and often jointly orchestrated major family celebrations – Christmas dinners, our father’s 90th birthday weekend – with Luli as chef, Lizzy as sous-chef. And we always delighted in performing together.. For Dad’s 85th birthday we hid Luli in a huge, festively-wrapped box behind his chair, and she popped out singing. For the 90th she revised an old song and we performed for the gathering – “F means that you’re fabulous dear Father, A says you’re amazing head to toe…”

“T tells you that you’re the tops and greater than any other daddy that we know”

Before my wedding to Joe, Luli spent a day with my friend Mary Anne preparing side dishes for the families’ burgers-and-oysters feast.

Luli loved Joe and Joe loved Luli, though at every visit he would have to endure one prolonged fit of sister giggles. Luli delighted in being outrageous and had a very childish sense of humor. Once she bought a whoopie cushion and kept shifting in her seat as Joe drove, producing long, wet-sounding farts from under her bottom. Joe tried politely to ignore them, but our giggles grew and grew till we were breathless.

Luli and I took care of each other. On a visit to Chapel Hill, I came down with a fever and bronchitis. For a week she fed me garlic soup and single malt as I lay on the couch with her cat on my stomach. After each of my knee surgeries she came to Florida to bring me companionship and cups of tea, and filled the freezer with delicious stews and pies to keep my family fed as I recovered. In her last year I spent a lot of time taking care of her in North Carolina. Those memories are both precious and very painful.

Joe visited Luli for a couple of days shortly before she died, when she was bed-ridden. He read to her from her copy of The Wind in the Willows. He brought her a brown plush mammoth which he had chosen very carefully from the large pile of mammoths at the science museum, comparing tusks and trunks to get one that was just right. Luli kept it in her bed, and now it is on Joe’s bookcase.

If you’ve lost someone important to you, you know that their death leaves a hole of a particular shape which nothing and no one else can fill. Luli and I talked almost every day, about family, friends, the dire state of the world, and our own troubles and triumphs. She loved my writing. She was eager for my novels to be published, outraged by the years of rejections. She would have been thrilled when I finally sold my first novel. I miss her; we would have shared all the aggravations, delights, anxieties and little triumphs of the time between the contract and the book launch.

I read The Pear Tree for the first time when I was writing this essay. It’s hard for me to read it, because it is about an old woman who tricks Death, and of course Luli didn’t. But it is filled with Luli; I keep going back to it to hear her voice. I am so grateful to her agent, Anna Olswanger, to Penny Candy Books, and especially to Marilyn Goodnight, the illustrator who added her beautiful paintings to Luli’s story.

It’s only fitting that Luli should have the last word, and here she is, again from her memoir:

I have stumbled into a purposeful life. The path may be crooked and overgrown, muddy and stony at times, but it’s there, and I walk it. I have always loved children’s books, and now I write them. Writing is a large part of who I am. I love knowing that my stories connect me to thousands of years of human history. A child comes up to me in a bookstore holding a battered copy of one of my books for me to sign, and I know that I have reached her imagination, nourished her dreams. I sign her book, and touch the hand of that first primordial storyteller who sat beside a hearth fire long ago and said, “Once upon a time…”

Buy THE PEAR TREE at https://www.pennycandybooks.com/shop/pear-tree

Sep 20, 2019

Arupa Freeman, aka Arupa Chiarini, is a painter, writer, and the guiding spirit of the HOME (homeless outreach mobile effort) Van. I call her the Fairy Queen because she has a mass of white-blonde curls, a loose dress, a huge Ha Ha laugh, and an invisible magic wand that invariably produces the right answer to the many quandaries that confront the HOME Van.

I knew the name Arupa Chiarini long before I met her. She and Bob Freeman were founders of the Acrosstown Repertory Theater – they ran it for ten years, writing, producing, directing, acting, administering. It was Gainesville’s out-of-the-mainstream theater venue. So Arupa was part of the Gainesville art scene, and though I occasionally attended plays, I was mostly part of the middle-class women’s do-gooder scene. She was everything cool and hip; I was everything stodgy, even though I’m still a hippie at heart.

I first met Arupa at meetings of the Homeless Coalition – she and her husband were volunteers at St. Francis House, our main homeless shelter. We were trying to create a Safe Space, where homeless people could hang out during the day. (St Francis and other shelters required residents to leave early in the morning.) Like all initiatives that include city government, it involved years of meetings, with everyone saying the same things over and over. It went on for a couple of years, and it resulted in nothing. But it allowed the city to say it was addressing the problem of homelessness.

image: shelterlistings.org

image: shelterlistings.org

At one point during the Safe Space campaign some firebrands decided we should camp out in front of city hall. I ran into Arupa at Goerings bookstore and confessed I was scared. Sleeping out on concrete in the middle of a crowd seemed like too much for me, and I had never been arrested. She was scared too, though she had been arrested once for lying down in front of a bulldozer that was about to knock down a tree.

picketing City Hall

picketing City Hall

The plan for camping dwindled into daytime pickets at City Hall. Arupa and I shared a two-hour shift, and that’s when we began to talk – about books, people, our lives, She grew up in Vermont, went to college in Oklahoma, spent years in an ashram in Carmel, and more years as an editor at McGraw Hill. After many years of talking, now I know she was intimidated by me, as I was awed by her. She saw me as the Episcopalian – everything snooty and proper and uppercrust.

image:Vermontdirtroad from Arupa’s blog

image:Vermontdirtroad from Arupa’s blog

http://vermontandotherstatesofmind.blogspot.com/ (This blog contains a lot of Arupa’s poetry, and some lovely pictures by her and others, as well as a Willie Nelson song.)

Arupa and Bob quit volunteering at St. Francis House when, after a new director took over, it became a place more concerned with regulating than welcoming homeless people. They invited a few friends to meet in their living room, to find a better way to help the people living in the woods, and that was the birth of the HOME Van.

We began in September 2002, with 283 jars of peanut butter, 283 loaves of bread, and $283. Arupa and friends rode around town hanging bags at the end of every trail into the woods, with bread, peanut butter, and a note saying we’d return. The drive-outs evolved until we were delivering homemade soup, food bags, medicine, clothes and socks, tents and other items to campsites and parks twice a week. This continued for over thirteen years. We never got government funding or a grant, but the community supported us, and every month I wrote thank you notes for the checks, large and small, that regularly arrived in the mailbox.

The HOME Van and Bob’s garden

The HOME Van and Bob’s garden

Four years ago Grace Marketplace, a homeless services center, finally opened in Gainesville. All the HOME Van volunteers were getting older, some sicker. So the Van stopped running, and Arupa, Bob and a few volunteers continued helping the poor and homeless with a food pantry. It’s officially open one day a month, when long lines of people wait patiently at the front door. But food bags and other supplies are always available for whoever knocks on the door, and there are several visitors a day to HOME Van Central, Arupa and Bob’s small house.

The house is half a block from the oldest community garden in Gainesville, six blocks from St. Francis House. The living room contains a refrigerator and shelves of canned food, dried soups, coffee, crackers, over-the-counter drugs and toiletries. Packed food bags, cartons of more food and supplies, tents, blankets and other donations make an obstacle course as we hurry to fill requests from the people at the door.

The walls are covered with paintings by Arupa and Bob, and Arupa’s easel is always at the ready. Bob keeps a flower bed going by their front walk. When their house was Gallerie Bob, there was an art fence festooned with found objects, but that has not been renewed in many years.

The art fence

The art fence

Arupa and I became close friends through the many years of the weekly drive-outs. She is one of the more literate people I know, particularly well-versed in philosophy, literary classics, and mysticism. She also has an encyclopedic mastery of old G-rated sitcoms and the lives of 1950’s celebrities. When Elizabeth Taylor died, Arupa delivered a long, loving eulogy to me and Larry, my sandwich-making partner at the kitchen table.

Her opinions are fierce and certain topics recur: the villainy of city officials, the imminent collapse of the economy and the environment, increasing poverty and cruelty, the limitations of allopathic medicine. (Arupa relies on homeopathic medicine and acupuncture, and was only sick twice in the years I’ve known her until a serious accident about three years ago.) She delivers her judgments with a conviction that makes my contrarian self silently argue the other side. These are all topics on which I have fuzzy views, often in line with hers, but too little knowledge to speak in the face of certainty.

In the early days of the HOME Van there were fewer homeless people in town, and Arupa and I had more room for frivolity. The first spring Arupa and I colored Easter eggs for the food bags. I took her canoeing down the Itchitucknee, one of many spring-fed streams near Gainesville. She included me in the local art world – once I performed in her play, Primary Colors, at an art gallery, and twice she invited me to read at Wild Iris, our feminist bookstore. For a perennially unpublished writer, these were thrilling occasions.

Primary Colors

Primary Colors

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ayAc-v_erk

Sometimes we’d find time for lunch on my backyard deck, or an evening together with Bob and my husband Joe Jackson. The conversation was exhilarating; sometimes I think that between them, Arupa and Bob know everything worth knowing.

The HOME Van is not what it was in the days of twice-weekly drive-outs, and I think we all miss it. In the HOME van we had the privilege of operating from our hearts and instincts, unlike the many good-hearted workers in agencies. We’d often hear from homeless friends that what they liked about the HOME van is we took them at their word. Tell us you’re hungry, we’ll give you some soup; and if there’s enough, we’ll give you seconds. If you need an extra food bag to take to someone else, we believe you. We would rather be snookered occasionally than treat everyone with suspicion.

Getting goodies at the HOME Van

Getting goodies at the HOME Van

Despite Arupa’s serious accident, followed by a life-threatening infection, she and Bob have kept that spirit alive. Though food pantry days are pretty frenetic, the three volunteers filling food bags and gathering supplies are always ready with a friendly word and listening ear. And on the other days, when only two or three may seek help, Arupa has the time to talk with people, listen to them. We deal with a lot of people who never come into the organized agencies.

Some people wear bracelets saying, What Would Jesus Do, though I haven’t noticed them acting particularly Christ-like. Many homeless people, and many people who don’t know Arupa, consider her a saint. She is anything but saintly, and HATES the accusation, as she hates receiving awards, but when I’m puzzled about helping people who are down and out, I ask, “What would Arupa do?” She has a clear moral vision that lets us focus on the basic question: how can I help?

From her I learned that if someone is hungry you hand them a sandwich; if they have blisters you give them a bandaid and clean socks. You meet people where they are, with respect and friendship. Some will find their way out of the woods, and you stand ready to support and help with that. Many will not, but if they are hungry they need food. Worthiness is irrelevant, and not ours to judge.

Bob and Arupa do most of the work of the HOME Van. She listens to stories and learns names, and the people who live in the woods have her phone number. When someone is sick, when the city is once again clearing a camp, Arupa knows who to call. She is the truest exemplar I know of my favorite saying: “Light a candle AND curse the darkness.”

ARUPA’S BLOG

For many years Arupa wrote a blog about our drive-outs and the people we encountered. I have been browsing through it as I work on this post,. I can’t stop reading; I’m laughing and crying. She writes beautifully, sometimes prose, sometimes poetry. It brings back so many memories, and her soul shines through. I’m giving you just one sample of the hundreds of posts, and encourage you to go find more.

from http://homevanblogspot.com

A CONVERSATION WITH ‘MOM’ (2009)

She got her street name because she takes care of people. I met her in the winter of 1994/1995. An overly zealous night manager at one of the local shelters evicted an old man with Alzheimers because he smoked in his room. It was a January night with temperatures in the thirties. After a few choice words about “Why the **** didn’t he just confiscate his cigarettes?” Mom took this old guy to her tent and kept him warm through the night.

A few months ago she actually managed to get me to do snuff outreach (with my own money, not Van money). She found an old, old man named Earle living in a shack near Tent City. Earle, who was well into his eighties, showed signs of senile dementia. He had a pack of half-starved cats and he himself was not doing so well.

Mom got some groceries and cat food from me and then said, “I need five dollars toward a tin of snuff.” Arupa: “You’ve got to be kidding. We don’t do snuff outreach.” Mom (tears running down her face): “He’s 86 and he’s been dipping snuff since he was 12 and he’s just sitting out there jonesing and jonesing…” Arupa: “Okay. Snuff outreach it is, coming right up.”

Mom and I were discussing the economy yesterday. She said that Day Labor had dried up so bad people aren’t doing drugs out in Tent City because they don’t have the money. I asked if she knew how business was for the ladies who work on SW 13th Street and she told me that it’s really down. Now, this is a side of the economic downturn you aren’t going to hear about on MSNBC – It’s BREAKING NEWS in the HOME Van Newsletter.

It got me to thinking about the Web of Life with the endless interconnecting tapestry of cause and effect. There is much suffering connected to this Great Recession, and will be for a long time to come. Can it be that there are also little miracles – lotuses growing from the mud – silently sprouting and putting forth roots? People planting vegetable gardens, people playing board games with their children because they can’t afford to go out – people in Tent City getting a “time out” from the nightmare labyrinth of doing drugs and turning tricks – a silent place where something new might grow. I believe in this.

BOOKS! GAMES! SOAP!

That’s what we need. Hallelujah for Spring and long evenings when people can read and play cards. This summer I am going to emphasize recreation in the Socks 4th Avenue section of the Van, with your help. Art supplies are good also, and anything else you can think of that is fun We are also low on personal hygiene products.

ENJOY THE WEATHER!!!!

Love and blessings, arupa

Aug 13, 2019

Over thirty years ago my late brother Richard and his wife Esther bought a house on Vinalhaven, an island in Maine. They spent every summer there, and as the years went by, four of their seven grown children and a granddaughter bought houses too.

Every summer at the end of July or beginning of August, children and grandchildren and great grandchildren gather in Vinalhaven for a week, filling all the houses, renting a couple more. We celebrated Richard’s eightieth birthday there, as well as three weddings. My oldest brother Don and his wife used to come from Connecticut to join the gathering. Now the drive is too much for them, but Esther hopes next summer they will fly.

I’ve always envied families who have a summer gathering place where they go every year. Joe’s parents always had a cottage at Crescent Beach in Connecticut, where his mother and aunt and their seven children spent a month in the summer, fathers coming out from the city for weekends. My friend Michelle sings with Other Voices; her song Bradley Beach perfectly conveys her childhood annual trip to the New Jersey shore, the kids crowded into the back seat, the summer thrills changing as they grew from toddlers to teens. Here’s the song

I went up to Vinalhaven several times before I married, but never felt quite comfortable there, and the trek from Florida was daunting. But since Joe and I married and Amanda came to live with us, we have usually managed to rent a house in Vinalhaven for family week. Now it is a magical place for me, a place where I have no cellphone service, wifi is scarce, lobsters are plentiful, icy water comforts my old joints, and beautiful views and beloved family are around every blind curve.

This year, because of Amanda’s school schedule, we couldn’t go for family week, but several family members arrived a couple of days before we left. And this year I went up by myself a week early to stay with my oldest niece Maria.

Like any trip to a magical place, the trip to Vinalhaven is a challenge. It’s full of unforeseen troubles and treasures, and the heroine must overcome many obstacles. I flew out of Gainesville at 7:15, scheduled to arrive in Portland about noon. I was going to spend the night at Luke’s house in Portland and drive to Rockland to get the Vinalhaven ferry the next day. (Rental car agencies and ferry schedules determined this plan.)

But at the gate in Atlanta they were calling for volunteers to take a later flight. They were desperate: the first volunteers got $300, but by the time I arrived it was a $700 American Express gift card good for six months. I thought a moment. I would get to Portand by five thirty instead of noon. Since neither Luke nor his daughter Frances was free my plan in Portland was simply to goof around. So I raised my hand to volunteer, headed to the desk, tripped and landed on my face. The only damage was the rug-burn on my cheek, and the mortification as four people gathered around the 72-year-old woman on the ground asking, “Are you sure you’re all right?”

After my scheduled flight took off with my checked bag, I sat at the empty gate and worked on an application for a 2020 writing residency in Washington – lots of 1200-word essays about me and my aspirations. Then a big thunderstorm rolled in, and all incoming flights were diverted from Atlanta, along with all the flight crews. Our copilot was in Birmingham; the rest God and Delta knew where. Every half hour or so we got a progress report. I went to a restaurant a few gates away and, because of the crowd, shared a table, sushi, and Scotch with a delightful university librarian from Cleveland. (Now that I think of it, I bet I could have scored a dinner voucher).

image: pixabay pexels.com

Back at the gate they were boarding. We were all settled in our seats when they announced an equipment issue, and we all unsettled and returned to the airport. An hour later we were back on the plane and in the air with that uneasy feeling one always has when flying on a plane with a recent equipment issue.

We arrived in Portland at 8:30. I retrieved my suitcase from the baggage office and rolled it up and down ramps to the rental car desk. I was exhausted, and a little worried to be driving in a strange city in the dark, but so glad to finally reach Portland. Then the nice young man behind the desk said, “Ma’am, this driver’s license expired last week.” Sure enough, it had. I had ordered another but it never arrived, and I’d forgotten about it. So I would have to take the bus from Portland to Rockland.

I rolled up and down more ramps and found a taxi with a friendly driver and a GPS to navigate through funky old Portland neighborhoods. When the GPS said we’d arrived, we couldn’t find the house number. The driver waited; “I’m not going to leave you here alone.” I called my nephew and his daughter with no success. A neighbor pulled into a driveway but didn’t know Luke. I climbed up to front porches looking at all the mailboxes, and finally found it. Climbed the long stairs to the second floor, took a welcome hot shower, and fell asleep.

Portland street

The bus ride from Portland to Rockland was uneventful. I didn’t worry about whether we would miss the last Vinalhaven ferry, because in my experience the bus always misses the ferry, and I know what to do. You take the North Haven ferry, find a boy with a boat, and pay him $5 to shuttle you across the water to the wrong end of Vinalhaven, where, if you can make proper phone connections with family, someone will meet you.

Maria did meet me – Luke, the only one with cell service, had left her a note. We went to Esther’s house for dinner and a very welcome glass of wine., and then home for bed.

Maria and I are only ten years apart; she is also a writer. We are kindred spirits and we bump along well together; Maria’s apartment in Washington Heights and house in Vinalhaven are two of my favorite writing retreats. The house is an old farmhouse about a mile out of town.

Maria’s house

My attic bedroom was up a narrow staircase with high risers and shallow treads. The one bathroom is downstairs, so a couple of times a night I was hauling myself back up the stairs with the help of a rope banister. But the bedroom was bliss and I slept soundly every night, after indulging myself in Wodehouse. (Maria has the complete collection, and it’s like a box of See’s chocolates.I read two of his novels in a row, and discovered that’s too much Wodehouse.)

Whenever I’m away from home, especially by myself, I sleep really well; perhaps because no home or family concerns call for my attention. I also work prodigiously. In two weeks in Maine I wrote a 15-page talk for a presentation in November, a short article about longleaf pine restoration, and a chapter of my fourth novel, as well as five 1200-word essays for the residency application, which I had to reduce to 1200 characters each when I realized I had misread the application form. It was flowing, and I was extremely happy.

At Maria’s I rose each morning about five and worked a few hours until she emerged. Her summer was very busy. She and her sister Ani had just finished revisions on a screenplay, a comic family thriller set in Eastern Europe. Luke, who is a cinematographer, was checking it over and correcting formatting before they sent it back to the producer. Difficult discussions were underway about casting. I loved being privy to all this glamorous drama.

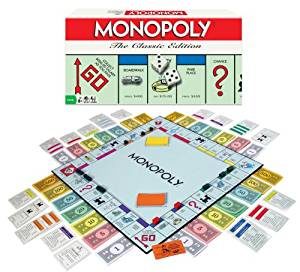

Maria’s daughter Adriana has a thriving yoga studio. Maria went to yoga every morning and took care of the eight-year-old twins every afternoon after their summer camp. A Monopoly game was in progress on the living room floor. Dylan had Park Place and Mia had Boardwalk; somebody had hotels on Mediterranean and Baltic. When they took a break from climbing trees, swimming in the quarry, exploring outside and writing in their nature journals, they sat on the floor fiercely disputing trades and deals.

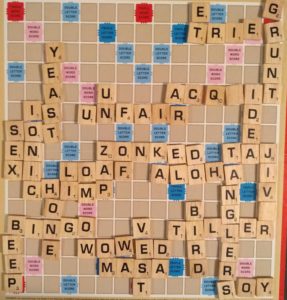

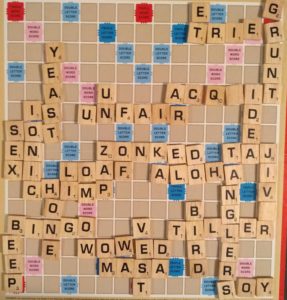

Every night Maria and I had dinner with Esther. The three of us took turns cooking. After dinner we played Scrabble. Maria won once, I won once, and Esther won five times. She is gleeful when she wins, her gloating barely concealed by sympathetic comments about our crummy letters.

One night Gabe joined us; I had barely seen him since his wedding to Adri. That night I learned how funny and interesting he is. He told hilarious stories of the Rockland to Vinalhaven plane – he commuted to his editing job in Boston when they lived on the island year-round.

We had tea with Maria’s friend Lorraine, joined by another friend, Alex. Lorraine’s house is modern and dramatic, with a fireplace of huge granite rocks fitted together like a jigsaw puzzle. It overlooks a cove, and we briefly sat on the deck before the mosquitoes drove us inside. Lorraine served tea, cookies and sweet raw scallops dressed with lemon and olive oil. I couldn’t get enough of them.

We had gratifying conversation about my book, and lots of talk about the New York arts scene. Maria and Esther both have friends among leaders of major arts institutions. The cultural elitist in me is awed. I’m also amused. Like many creative people, my family tends towards shabby and broke, yet they hobnob with people who attend museum galas.

Without a car and with family so busy, I made frequent use of Vinalhaven’s lone taxi. Jeanne would pick me up at the library on a moment’s notice. Better than that, we instantly discovered we are kindred spirits. For many years she taught art and English at the Vinalhaven school; she has writing aspirations and a strong lefty-feminist streak. I was foolishly proud to have made my own friend on Vinalhaven, instead of just tagging along to meet my family’s friends.

Maria’s husband Chuck and their son Cristian were arriving Saturday, so I moved into our rental house. It was very sleek and new, and quite cheap because it was several miles out of town and not on the water, but on a steep rise above the road, looking out into fir trees. It didn’t have the charm of my family’s old farmhouses and cottages, but it was set up perfectly for everyone’s privacy. I had a happy night and morning all by myself, and then Jean took me to the last ferry to meet Joe, Amanda, and my son Eric.

We amused ourselves together and separately. Joe and I swam in the quarry and the icy Basin. I swam in the Bathing Hole, muddy at low tide but cold and salty. We went for a short hike together, and he went kayaking twice – eagles and ospreys and seals.

image daniel lee at pexels.com

Eric was sick and couldn’t do all the vigorous Maine things he loves. Though he’s very self-sufficient, I’m sure my fretting was curative. Amanda slept a lot and immersed herself in wifi, as she does at home. But at night she went off with the older, college-age cousins.

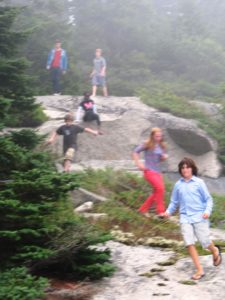

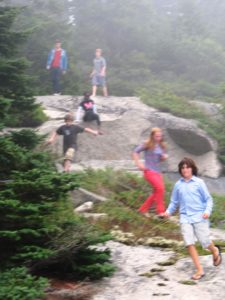

Long ago, when Amanda was nine, the older cousins went rock-climbing. They told the young ones they were going to talk about adult things; if they didn’t know what puberty was, they couldn’t come. Amanda knew all about puberty, but poor 7-year-old Gus and his little brother were excluded. From then on, Amanda was part of the big kids. Now it’s not rock-climbing, but hanging out at somebody’s house until early morning. I’m glad she’s included.

2012 – children flow downhill

As family members arrived, we shared dinner or desserts, and then played games. The Minister’s Cat – everybody claps in rhythm, and we go around the room, “The Minister’s Cat is atrocious, The Minister’s Cat is beautiful, The Minister’s Cat is cadaverous….” If you can’t think of a word or keep up with the rhythm, you’re out. The adverb game: one person leaves the room, and the group decides on an adverb. Ze returns and tells people to perform actions – Ben, write a letter – Luke, wash your hair – in the manner of the adverb. Then ze has to guess the adverb. Don polishing Joe’s shoes amorously is a sight I’ll never forget.

On our last night I prepared the family dinner – there were 15. I made a salad and my much-praised beef stew in a newfangled oven that had me cursing. For some reason the potatoes and carrots weren’t thoroughly cooked, but no one complained. People brought ice cream bars, popsicles and cookies. Afterwards some played a wild card game called spoons – I don’t know how it worked, but every once in a while there was a mad scramble to grab a spoon from the table. In another corner was a more sedate game of Uno.

I love that there are no televisions in my family’s houses; that people don’t hide their faces behind their phones. I love that people from 7 to 87 play nerdy games with enthusiasm and hilarity. I love the harmonizing singing sessions, with songs old and new. I love that writing and art are seen as essential endeavors. This is my family’s culture, and I feel at home in it, though I have moved into a different world.

To take your car on the ferry from Vinalhaven, you must call at 5:30 AM the day before. You must arrive half an hour before departure; one minute late, you’ll go to the back of the line, and your car won’t make it on to the ferry. We took the 8:45 ferry, which left at 8:15 because Main Street in Rockland was going to close for the Lobster Fest parade, and we were in line five minutes early. Maria, Luke, and Michael showed up to welcome Paul and his new wife and stepdaughter coming in at 7:45 and.say goodbye to us.

I always get tearful riding away on the ferry through the cool morning, looking back at the harbor with its lobster boats. So many memories of so many summers: Richard and Esther sitting on the porch in the morning, everyone dropping by for coffee and conversation. Children, and all of us, swimming in the quarry. Long talks with Esther over coffee, and her annual Summer Open Studio, where Joe and I always fall in love with at least one painting. Luli at the lobster roast the night before Luke and Lisa’s wedding, sitting on the ground and eating five lobsters plus two tails. Lobster rolls at Greet’s Eats, where the boats pull in and dump their lobsters into the tanks. My nieces and nephews grown into middle age, their children going to college, having children of their own.

Amanda and Frances – sunset swim in the quarry

Lobster rolls with Don

They are sweet tears of memory and sad tears of loss. Richard died around Thanksgiving five years ago; Luli died two years ago on his birthday, August 16. Only Don and I are left. Every death leaves a hole with a particular shape that no one else can fill. But I’m so grateful to have my two sisters-in-law, Esther and Doris, and that my nieces and nephews have taken me in as a kind of sister. Now we have more family, as Verushka and Leilani join my great-nephew Paul. I hope I will get to know them, and I plan to travel to my magical place for many years to come.

A magical place

image: shelterlistings.org

image: shelterlistings.org picketing City Hall

picketing City Hall image:Vermontdirtroad from Arupa’s blog

image:Vermontdirtroad from Arupa’s blog The art fence

The art fence Primary Colors

Primary Colors Getting goodies at the HOME Van

Getting goodies at the HOME Van