Aug 16, 2021

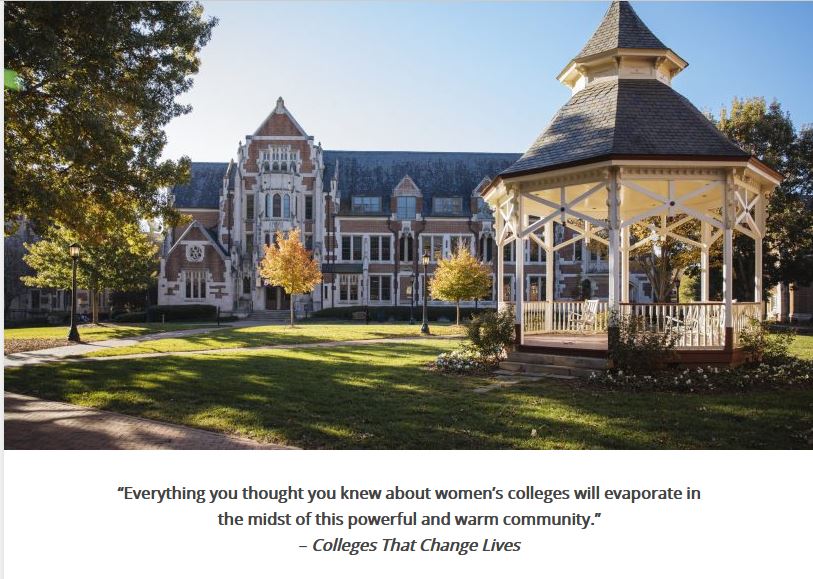

Our granddaughter has lived with us eleven years. Tomorrow we drive to college outside Atlanta with mountains of stuff in two cars. We’ve all weathered tough times and plenty of heartache, but we’ve come out wiser, with our love stronger. She is an extraordinary young woman.

They’re all going to college!

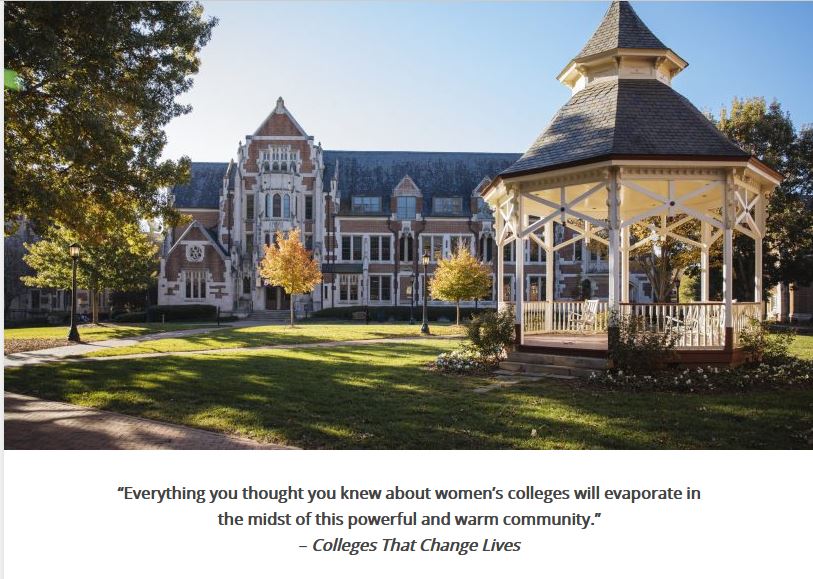

Agnes Scott College

I was finishing a chapter of my novel (I think I am the slowest writer in the world) when I got distracted looking for a version of Bridge Over Troubled Water that I could share with her. I have always thought of this as a song from one friend to another, in the Lean on Me category. But my singing partner and I were working on it last week and came to the third verse, which Paul Simon wrote in the studio because his producer insisted on one more verse: “Sail on silver girl, sail on by, your time has come to shine, all your dreams are on their way, see how they shine… “ I controlled myself as we practiced, but broke down the next morning, when I cried and cried.

Photo by Johannes Plenio from Pexels

I’ve never before suffered from empty nest syndrome. My feelings have always been closer to “Free at last!” But this time, maybe because I’m older and more tender-hearted, maybe because she has overcome so many obstacles, I seem to be heading straight into grief. We will certainly miss her – she is extremely lively and funny, and at dinner I sometimes have trouble eating because we laugh so much.

We lose our children over and over as they grow – the round-headed baby with the huge eyes, the three-year-old exuberantly climbing the monkey bars, the nine-year-old off to the father=daughter dance with Grandpa, wearing the rose corsage he gave her, the eleven year old posing so proudly in her safety patrol belt – they and so many more are long gone, leaving nothing but memories and photographs.

My life will be my own again; I won’t be responsible for anyone but me. My time is my own; I hope I won’t squander it. In the years of raising her I have become a worrier, an anxious woman. (It’s possible I always was, but I don’t think so.) I am quite sure I won’t recover entirely, but based on past experience I’m also sure that there’s a fair amount of ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ When a child is far away most of the daily troubles resolve themselves before we know about them.

Worry makes wrinkles

I began this essay a few days ago. Since I began writing it I’ve been an explosive mix of grief, excitement, worry, pride. Raising children is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

Mar 25, 2021

I once wrote that the main thing I fear about aging is the death of more and more friends and family. That was eight years ago, and now at 73 I have reached the time of losses. I have lost a brother, a sister, and seven friends. The experience is as profound and hard as I feared. Each death leaves a hole which no one else can fill, in a shape peculiar to that person, like a missing piece in a jigsaw puzzle. We hear about the deaths of old friends whom we have little contact with, and it sends us back to earlier times in our life. But the people who are part of our present life – whom we talked to daily or weekly – whenever we turn a corner we encounter their absence again.

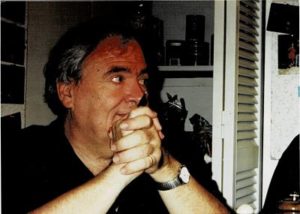

Brother Dickie

Sister Luli

I would like to say I am learning to deal with loss, but I don’t know what that means. The idea that in a year after a death you will have folded up the sorrow and put it in a drawer where you can visit the memories doesn’t ring true.

Grief in a drawer

My sister Luli died three and a half years ago, leaving many writings and cartoons. My friend Arupa died a little over a year ago. She was a writer, painter, and founder of the HOME Van; she had asked me to be her literary executor. I carried home cartons and two file drawers with her writings, along with the remainder of her paintings. I plan to compile her writing about homelessness into a book and sell it to benefit homeless services, then share some of her remaining work on Facebook or on this blog. A writer wants to be read.

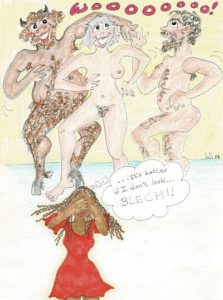

Birthday card by Luli

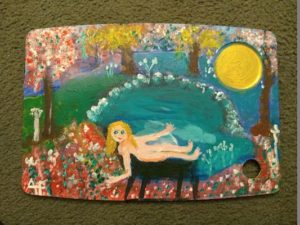

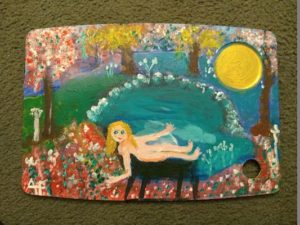

Painting by Arupa

Early in March I finally began reviewing Arupa’s work. Luli’s birthday was March 4, and she haunted the work – when I took a break from Arupa, I would go to Luli’s writing. My friend and my sister had a lot in common (besides their fondness for drawing nudes). Both bore scars from childhood and survived trauma, confusion and pain to become women who were larger than life. They were both writers and visual artists. Luli’s huge, generous heart had a genius for friendship, while Arupa shared her heart and her last twenty years with people who are homeless.

The legacy left by an artist and writer’s death gives us more than memories; we can visit their voice and vision whenever we like. They come back so clearly, with an intimacy and honesty we may only have glimpsed when we were together. But it is a mixed blessing. All that we lost is there before us, right on the page, and we can’t offer comfort, ask questions, share our own stories.

Mourning doesn’t end after a year. As time goes by, grief, at first an acute condition, becomes chronic, flaring up from time to time when we bump into a memory. But I suppose after a few years we become used to the jigsaw gaps, accustomed to grief. Sometimes we deliberately visit the memories; sometimes we run from them. But after someone dies, all we have are memories. If we flee the memories because they carry sorrow, we lose a loved one twice.

Missing pieces

About Arupa: The Fairy Queen

About Luli: Sisters Two

Sep 30, 2020

I am about as fortunate as one can be in these unfortunate times. I do not live alone, but with my husband and granddaughter, and we get along well. I have a garden, a swimming pool, the writing work I love, and no money worries. I don’t have a job that demands I spend most of my time virtually, nor small children whom I must help with virtual school. The only direct impacts I’ve suffered from Covid 19 are a minor one, being unable to dine out, and a major one, missing the annual gathering of family in Maine.

Blue glory vine. Image: purple trumpet flowers with yellow throats, swimming pool in background

My family in Maine. Image: Nine smiling middle-aged and old people at picnic tables in front of lobster shack

Nevertheless, I get the blues. I feel dark clouds looming just behind me. I try not to spend all my time on them – I use an app to block social media for twenty four-hour stretches, don’t read news at the beginning or end of the day, listen to music more than to NPR.

Image: white butterfly logo on green background with message: You are free. Go do great things. website: freedom.to

But there is no app to suppress my thoughts, and other people’s troubles haunt me. The people who have lost their jobs, who will lose their homes. The kids who graduated from high school or college in the spring, into a world of few possibilities. The teachers, struggling to teach simultaneously in person and by Zoom, maligned in letters to the editor and on social media. All the essential workers, fearing for their health. The hospital workers fighting death daily. The people on ventilators, dying alone, and their families. Nursing home residents and prisoners.

Lowell Correctional Institution (in August, 900 of 2200 inmates tested positive). Image: cinderblock building with coiled razor wire.

And behind that cloud of sorrow is shame. After years of imperialism abroad and inequity at home, I didn’t think I had any patriotism left until we failed so miserably in this latest trouble. Our government is a terrifying disgrace.We have managed to turn public health into a divisive political issue, and we can’t even work out how to produce enough protective equipment. Every couple of weeks a cellphone records another murder of a Black person by a police officer, usually followed months later by a slap on the wrist, or less, for the killers. Above it all, a looming cloud of fear. What will happen in November? And what will happen in the months between the election and the inauguration?

image: sign “2020 Vote Election Day” blue and red letters, flag logo

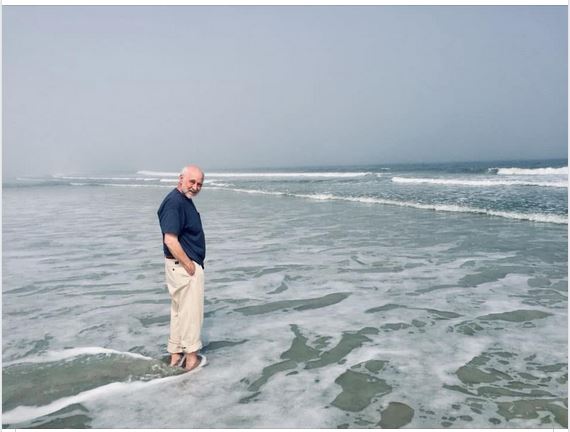

Well into the summer I was faithful about routines. I worked out every other day, swam, weeded in the garden. I revised my novel twice at my publisher’s suggestion, wrote five chapters of another novel, sent a query to an agent, worked on my website. Mostly confined to my house, I almost achieved the productivity of a writers’ retreat. Then sometime in August my energy flagged. Now I have turned to music.

In my writer’s retreat. Image: white-haired author in bed under red blanket working at laptop, leaning on huge teddy bear with yellow rubber chicken dangling above

I have long been a fan of Black gospel, with its rocking rhythms, powerful harmonies and soaring solos. I listen to it on long car rides. When I work out I listen to gospel and sing along with any breath I have to spare. It’s not just the music; the words cut right to my heart. Some songs make me jubilant, others make me cry. An atheist, I’m not sure why gospel moves me so profoundly, but I think it’s the mixture of joy, sorrow and hope.

image: pile of CD’s: Clara Ward, 2 gospel compilations, Aretha, Silvertones, Dorothy Coates

Emily Dickinson called hope “the thing with feathers,” a bird that sings “sweetest in the Gale” and keeps us warm. I think we hold onto it even when we don’t believe. The darkest thing is despair. It leaves us unable to move, unable to act. Even delusional hope lets us move forward.

Despair. image: woman in jeans seated on floor against gray wall in empty room, knees drawn up, head rests on arms. Photo by pixabay at pexels.com – resized

Like gospel, classical choral music moves me deeply. I used to sing in large choruses. To hear many voices sing complex music is thrilling; to stand in the middle of the ocean of glorious sound and add your voice is sublime. In August I took an online course in choral repertoire that focused on requiems. I was already familiar with the Mozart; when the class was over I decided to study the Berlioz, Britten and Brahms.

I printed out the librettos with translations. It’s hard to follow along – unlike gospel, in classical works the music is more important than the words, and composers often stretch syllables over many measures. But reading the text gives me some sense of the meaning, and I’m slowly learning to recognize each movement.

The Mozart and Berlioz are based on the Roman Catholic mass for the dead. They focus on the Day of Judgment and the horrors of Hell. They plead for forgiveness and eternal rest. The Brahms uses biblical texts to offer consolation to mourners. It acknowledges grief, promises joy, and doesn’t get grisly about Hell. The Britten War Requiem mixes texts from the mass with bitter poetry by Wilfred Owen, killed in World War I at age 25.

Two kinds of Hell. image: detail of The Last Judgment by Jan VanEyck – skull looms over naked tortured souls

Two kinds of Hell. image:black&white photo of WWI soldiers going over the top of trench in Battle of the Somme, 200,000 British soldiers were killed on the first day.

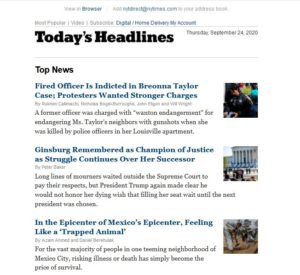

Recently I broke my cardinal rule, and read the New York Times first thing in the morning. It was truly disheartening, especially Thomas Edsall: “Five things Biden and his allies should worry about.“ I was already worrying about most of them. It made me angry, made me wonder whether the Rump has taken over everything, and has the Times helping him in his strategy of sowing chaos, confusion and fear.

image: Sept 24 NY Times headlines re Breonna Taylor indictment, death of Justice Ginzburg, Covid 19 in Mexico,

So, after crushing myself with bad news, I turned on the gospel music. The Staples Singers told me “I know a place where aint nobody worried,” and promised “I’ll take you there.” The Mighty Clouds of Joy urged me to take a load off my mind and “Ride the Mighty Glory.” I danced, lifted weights, slam-balled, squatted. And when Shirley Caesar sang that great tearjerker for moms and grandmas, “No Charge,” I cried the tears that have been building for months. Then I jumped in the cold pool and sang, “High upon the mountain, leave my sorrows down below.”

It all energized me. I wrote for a couple of hours, then sent an email to the Democrats offering to volunteer. I weeded until I got too hot. I made a carrot cake as a treat for Joe the law teacher and Amanda the high school senior, who are both dealing with HyFlex – the unwieldy scheme for teaching students online and in person at the same time.

The War Requiem is next on my study agenda. When we studied it in class it sent me back to Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, about the British psychiatrist in World War I who treats soldiers sent home with shellshock so that they can return to the trenches. I read the bitter war poetry of Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, both characters in Barker’s novels. Like the Britten, Barker’s trilogy is a brilliant anti-war work of art.

Wilfred Owen. Image: young man in soldier’s uniform with mustache and slicked down black hair parted in the middle

I learn most of my history from fiction. We’re living in a very hard time, but human history is filled with hard times, when fear, confusion and conflict reigned. Lies flew from all sides. People struggled to understand, to find meaning, to figure out what to do. There were many villains, but there were also heroes. My granddaughter asks me why I like to read about hard times, and I tell her it moves and inspires me to see how people survive and sometimes triumph over trouble. It gives me hope.

The thing with feathers. nimage: European robin, gray bird with rufous head and breast, singing on branch against gray sky. Photo: Pixabay at pexels.com

Jun 18, 2020

Bob Freeman died on May 31 at age 79. He was a painter, theater director and producer, gardener, deep thinker, sardonic humorist, dear friend to many, and devoted father to three now-grown children. To me he was the backbone of the HOME Van and, after his wife Arupa died five months ago, also its head and heart, serving the homeless and hungry out of the food pantry in his living room with just a few volunteers to help.

I’ve known Bob eighteen years, but we grew closer after Arupa’s death in December. Working with him on the HOME Van and to prepare for a memorial art show and poetry reading for Arupa, I came to know his generous heart. We were going through boxes of Arupa’s papers when someone came to the door for a food bag. Bob took it to him, and then came back in the room and took his jacket from the closet. “Bob, you can’t give him the jacket off your back.” “Oh, I can get another.”

An Arupa painting

Gia, Ezra, and Peter, Bob’s three children, came to town to arrange the memorial service. Gainesville was on the fringes of tropical storm Cristobal and the heavens were weeping for Bob, so Joe and I set out with umbrellas to the gathering place, an early 20th Century house with porch and turrets. I saw some people I knew and many I didn’t. We gathered six feet apart on the lawn and porch, raising and lowering umbrellas as needed. We signed the guest book, one of Bob’s sketch books that he always carried, filled with pencil and watercolor drawings. A friend played a long mournful tune on her violin. Another read a letter from Anna, Bob’s first wife and mother of the children. All three children spoke – they had an idyllic hippie upbringing with Bob.

A few Jazz Bandits

We walked to the community garden, led by three brass instruments from the Jazz Bandits playing Swing Low, I’ll Fly Away, and many other lively gospel tunes. It rained, it stopped, it rained, it stopped, and then it came full force. We huddled under a couple of carports, still doing a pretty good job of distancing. Bob would have enjoyed our gathering under the No Trespassing signs, and the faint odor of marijuana.

When the rain subsided from torrential to steady, we walked on, past the Matheson Museum and through Sweetwater Park to the community garden. I don’t know how many plots are in the garden, but it’s filled with collards, kale, tomatoes, sunflowers, and exuberant weeds. Next to the plots is a grassy stretch, and there Bob’s children planted two peach trees, with Bob’s and some of Arupa’s ashes (the rest are going to Vermont, Arupa’s native land.) The children talked of their times playing in the garden. I read a poem by Shmal, one of the main HOME Van volunteers, who has moved to Seattle to be with family.

McRorie Community Garden

From the garden we went across the street to hear the Jazz Bandits play at band-members Jackie’s and Mary’s house – they live next door to HOME Van Central. We milled in the street, pretty much social distancing, but lowered our masks to eat Bob’s collards and drink Jameson’s whiskey. (Bob was a whiskey drinker.)

Every day I think of something I want to ask or tell Bob, and then remember I can’t. And Bob’s death means the end of the HOME Van. We all wondered whether there was a way to keep it going, but Bob and Arupa’s house was HOME Van Central, and the project – first the drive-outs and later the food pantry – was full-time unpaid labor.

We started the HOME Van eighteen years ago; it hurts to think of it dying. Guided by Arupa’s vision, we were tiny and improvisational, meeting people where they were, and doing whatever we could to help them, always in a spirit of friendship and a bit of anarchy. I am just at the age where people are beginning to fall around me, and each death punches another hole in my world in the unique shape of someone I love. The loss of the HOME Van does the same, for me and for Gainesville.

The Van

Home Van Centr

Jan 8, 2020

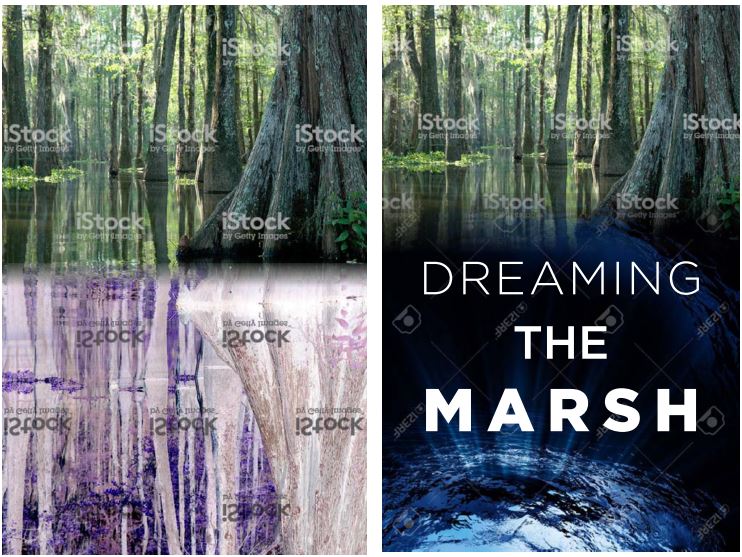

Four months ago, after thirty years of hoping and trying, I finally published my first novel, Dreaming the Marsh. This is for those who yearn to transition from Writer (unpublished) to Author (published). A year ago, in “Happiness,”I described the early pre-publication work: joining the Authors Guild, hiring a publicist and website designer, editing the manuscript, struggling to get blurbs. https://elizabethmccullochauthor.com/happiness/

In the months that followed, Emma, my publicist, taught me how to use Twitter, Instagram, and Goodreads. She arranged interviews on radio, TV, blogs, and print media – for an unknown author from a tiny press I had a lot of interviews. The website designers, Jennifer and Kat, guided my decisions in website design and patiently taught me how to maintain the site. Unlike many publishers, Joan Leggett consulted me on every detail of cover design. I was very pleased, until suddenly I wasn’t. I panicked and decided the cover was terribly wrong. Joan was calm and soothing; I suspect every one of her authors has a gut-wrenching panic episode before the book launch. She told me I should wait to see the ARC( advance review copy), and then we could consider changing the cover if I didn’t like it. I loved it, and many people praised it without prompting. We didn’t change the cover.

Two early cover image ideas

There has been some frustration, some anxiety, but there has been so much happiness in this year. As soon as I received the ARC, I went over to my friend’s house for a cup of tea in her garden. I handed her the book and pointed her to the dedication, which I wrote when I finished the first version, and kept secret for thirty years: “To Mary Anne Hilker, friend and first reader.”

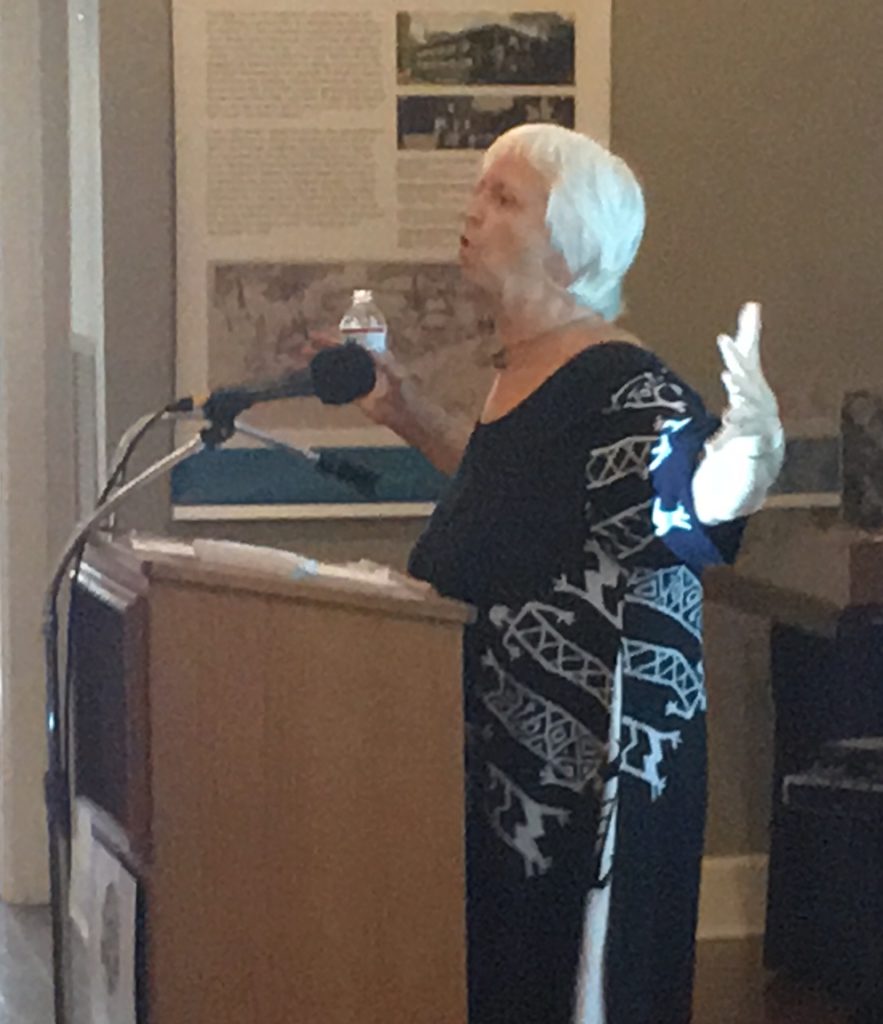

My book launch was in September at the Matheson History Museum. My gang of friends, the Muumuus, served refreshments of homemade cookies, coffee, and lemonade. Another friend, John Polkowski, made a music mix to play before and after my talk. Sandra Lambert, my writer-friend and mentor, advised me to tell about my work as a writer, and about the book. I looked out over the audience – it filled the hall and spilled into the next room. I knew many of them, and I felt their love and support as I talked about the long years that had finally brought me to this place.

It’s Yuuuuge

Twisted Road’s Joan sells books

Aside from interviews and blog reviews and word of mouth, I planned to promote my book with presentations at retirement communities. I had contacts at two of these, and arranged to give an hour presentation with a slide show about Payne’s Prairie, which inspired the book.

The first slide

It was a lot of fun, and the audiences were large and enthusiastic. I arranged another one in Gainesville, and one in Palm Beach, and I intended to drive around Florida giving my talk. However, I am having second thoughts.

On the one hand, I enjoy it, and I’m spreading the word, which may spread further to residents’ families and friends. I’m providing entertainment, which gratifies the do-gooder in me. On the other hand, at each presentation I only sell a couple of books; few people bring their wallets, though I believe some may later buy on Kindle. My do-gooding has always been aimed at the poor rather than the prosperous, and there are no poor people in these communities. I’m still figuring this out.

I spoke at a retirement community in Sleepy Hollow, NY

Another target I’ve chosen is book clubs. My publisher gives an extreme discount to book clubs for a purchase of ten or more copies, and I’ve offered to visit in person or virtually. I have visited one book club and have five more lined up. I’ll know more when I’ve done those, but so far it’s way too much fun to forego, regardless of whether it results in sales. A small group of engaged readers who want to talk about my book – what’s not to like? And three of the coming engagements involve wine and food.

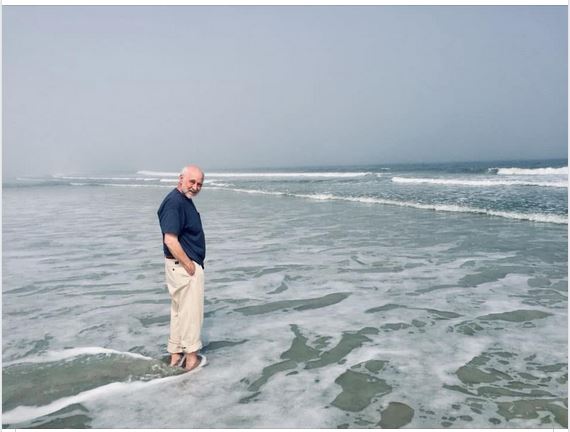

Finally, there was the presentation at the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings homestead at Cross Creek. Mary Anne is a docent there, and she introduced me to Geoff the ranger. Geoff had been wanting to bring writers to the park, since Marjorie wanted it used to nurture writers, and he arranged this as the inaugural event.

I asked Lars Andersen, a kayak and nature guide who wrote Payne’s Prairie, the source of most of my knowledge, to join me. It was a beautiful sunny day, the park volunteers had made cakes, cookies, and roselle tea, the Front Porch Backsteppers (Eli Tragash and Virginia Carr) played fiddle and guitar. Geoff, introducing me, spoke of the long history of writers reading their work when Marjorie lived there, and welcomed me into that group. And Lars described how the ancient people of the Prairie revered the story-tellers who preserved their history, and said I was carrying on that tradition.

Lars and me

The day after Thanksgiving I went to Paynes Prairie. It was a blue-sky-fluffy-clouds afternoon, with lots of people walking the boardwalk, families visiting from out of town, awed by alligators and birds. I was leaning on the railing watching the limpkins when a family approached and the woman said, “I know you from somewhere.” We stared at each other, trying to figure it out, and then she said, “You’re the author! We heard you at Cross Creek.”

‘You’re the author.’ What lovely words to hear. Yes I am, after all these years. I hoped to get some press for being so old when my first novel was published, but nobody considered that interesting. I‘ve just read that Delia Owens is 70, and has sold 4 million of her debut novel, Where the Crawdads Sing. Whenever I yearn to be a bestseller too, I remember what I wanted through all those years of writing and trying to be published: I wanted people to read and like my book, and they do. I wish there were more of them, and of course I’m aware that I only hear from fans – people don’t go out of their way to call me up and say, “I read your book and I didn’t like it.” But my long dream has come true, and I believe I am happier than I have ever been.

Oct 17, 2019

Luli Gray was an adorable and spoiled little girl, a brilliant student who barely made it through high school, a confused and very young bride, a vagabond in Europe, a waitress, file clerk, janitor, aspiring actress, professional cook, and finally in her mid-forties a successful writer. Most important to me, she was my sister. If you are lucky enough to love a sister, you know that the bond is deep and strong. You share memories back to your earliest days, and the giggling girls are still there in old age.

Luli and Me

After Luli died, as I searched through Windows Explorer for pictures, I came across the draft of an essay she wrote in her late fifties. She had heard Susan Farrell, the great ballerina, talking about her life. Farrell had wanted to be a dancer since childhood, and she worked hard and steadily to follow that path. She had no regrets. Luli envied her. She wrote:

I have backed into my life like a bird into a propeller blade, squawking and flapping. Sometimes I have felt torn apart like that bird, thinking I would never fly again, or even survive. And if someone asked me, ‘Do you have any regrets?’ I would say, ‘Yes. Many.’ I do not dwell on them very often, and sometimes I suspect that my disasters as much as my successes have made this odd Mulligan stew of talent, terror, laughter, despair, joy and rage that is me. Sometimes I quite like the stew. But there was no clear path, ever.

Luli was finally making an adequate living as assistant to a food writer, with side gigs as a recipe developer, when she began writing seriously.

I scribbled short stories and sent them to magazines. Lots of stories. Lots of magazines. Lots of rejections. Apparently, nobody wanted my stories. I kept on writing. I got up at 5AM six days a week so I’d have time to write before leaving for work. I sent out stories; they came back. I sent them out again. One day, after a year of this, a story began to grow. It had a dragon in it, and a child. Could I possibly be writing a children’s book? Yes. Holy cow.

I wrote the first draft at white heat, in less than two weeks. I wrote and rewrote and sent it out to a few agents. Three weeks later I had an agent and a book contract with a major publisher. Finally, after more than forty years, I have found a passion that sustains me, a desire to keep reaching for my unexpected, unattainable star.

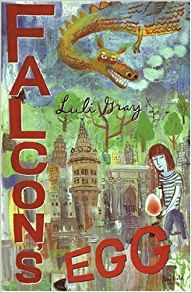

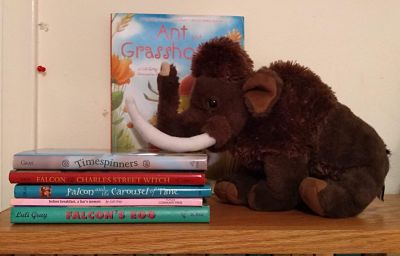

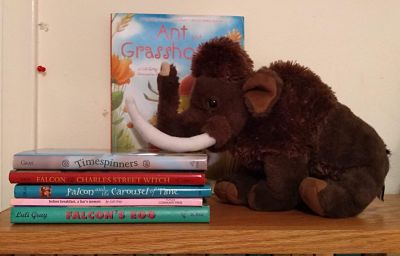

Luli followed the first novel, Falcon’s Egg, with a memoir of our father that she drafted in a 24-hour writing contest, which she won. She returned to Falcon with two more books, and then wrote Timespinners, a book about a brother and sister whirled away to the good old days of Neanderthals and wooly mammoths. An auto-didact who read widely (she re-read Moby Dick, including the whaling sections, every couple of years), Luli was fascinated by Neanderthals. She turned to Aesop, and wrote Ant and Grasshopper, a picture book with beautiful illustrations by Giuliano Ferri. This took years. As any writer knows, telling a story in 750 words is a lot harder than 75,000.

Luli was her own most severe critic. She acknowledged the worth of Falcon’s Egg, a Newbery Notable, but dismissed the rest except for Ant and Grasshopper, her first picture book. It helped that our late brother Richard, a prominent book critic, told her, “This is a perfect book.”

Now we have another book from Luli. I won’t call it the final book, because her agent has two more manuscripts of transformed fables to peddle, and as Luli tells us, there will always be Hope in the world.

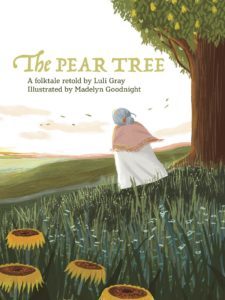

Luli learned the Spanish folk tale of Tia Miseria y La Muerte from Richard’s wife Esther when she lived with them and their seven children in Madrid. She transformed it and made it her own, replacing Miseria (misery) with Esperanza (hope). In Luli’s version, though Death must do his necessary job, there will always be Hope in the world. She worked many years to realize her vision of The Pear Tree, but she couldn’t get it published. A picture book about death? No way.

About nine months after Luli died we heard from her agent: Penny Candy Books wanted to publish The Pear Tree. Crying, I stormed around the house. Why couldn’t this have happened before she died? She wanted it so much, and she would never know. It took a few days, and many emails with her close friends, for me to begin to rejoice.

Luli’s books delight me, but she was not just a writer. Luli was a cook, cartoonist, cat-lover, and above all, generous, loving friend. She had charisma, compounded of eccentricity, humor, and her avid interest in all sorts of subjects – gypsies, lepers, Neanderthals, nuns, books, cats, food, gardens – and especially other people.

Luli’s garden – old shoes are excellent planters

She made friends everywhere and all the time. Some were friendly acquaintances, like the bus drivers with whom she shared gardening stories or the copy store clerk who helped her print her homemade greeting cards. She would meet women at the gym, arrange to meet for coffee, and soon progress to lunches that lasted several hours. And then she had her long-time friends, her New York friend Mary Jane, her neighbor Margaret, Kathryn Hubbell, the group of writers she called the coven, and many others, who came together as Friends of Luli in the hard last year of her life.

Luli and I had the special friendship of sisters. We shared a family history, family culture, jokes and references that only we could understand. We shared love, laughter, and outrage. We visited each other several times a year, and often jointly orchestrated major family celebrations – Christmas dinners, our father’s 90th birthday weekend – with Luli as chef, Lizzy as sous-chef. And we always delighted in performing together.. For Dad’s 85th birthday we hid Luli in a huge, festively-wrapped box behind his chair, and she popped out singing. For the 90th she revised an old song and we performed for the gathering – “F means that you’re fabulous dear Father, A says you’re amazing head to toe…”

“T tells you that you’re the tops and greater than any other daddy that we know”

Before my wedding to Joe, Luli spent a day with my friend Mary Anne preparing side dishes for the families’ burgers-and-oysters feast.

Luli loved Joe and Joe loved Luli, though at every visit he would have to endure one prolonged fit of sister giggles. Luli delighted in being outrageous and had a very childish sense of humor. Once she bought a whoopie cushion and kept shifting in her seat as Joe drove, producing long, wet-sounding farts from under her bottom. Joe tried politely to ignore them, but our giggles grew and grew till we were breathless.

Luli and I took care of each other. On a visit to Chapel Hill, I came down with a fever and bronchitis. For a week she fed me garlic soup and single malt as I lay on the couch with her cat on my stomach. After each of my knee surgeries she came to Florida to bring me companionship and cups of tea, and filled the freezer with delicious stews and pies to keep my family fed as I recovered. In her last year I spent a lot of time taking care of her in North Carolina. Those memories are both precious and very painful.

Joe visited Luli for a couple of days shortly before she died, when she was bed-ridden. He read to her from her copy of The Wind in the Willows. He brought her a brown plush mammoth which he had chosen very carefully from the large pile of mammoths at the science museum, comparing tusks and trunks to get one that was just right. Luli kept it in her bed, and now it is on Joe’s bookcase.

If you’ve lost someone important to you, you know that their death leaves a hole of a particular shape which nothing and no one else can fill. Luli and I talked almost every day, about family, friends, the dire state of the world, and our own troubles and triumphs. She loved my writing. She was eager for my novels to be published, outraged by the years of rejections. She would have been thrilled when I finally sold my first novel. I miss her; we would have shared all the aggravations, delights, anxieties and little triumphs of the time between the contract and the book launch.

I read The Pear Tree for the first time when I was writing this essay. It’s hard for me to read it, because it is about an old woman who tricks Death, and of course Luli didn’t. But it is filled with Luli; I keep going back to it to hear her voice. I am so grateful to her agent, Anna Olswanger, to Penny Candy Books, and especially to Marilyn Goodnight, the illustrator who added her beautiful paintings to Luli’s story.

It’s only fitting that Luli should have the last word, and here she is, again from her memoir:

I have stumbled into a purposeful life. The path may be crooked and overgrown, muddy and stony at times, but it’s there, and I walk it. I have always loved children’s books, and now I write them. Writing is a large part of who I am. I love knowing that my stories connect me to thousands of years of human history. A child comes up to me in a bookstore holding a battered copy of one of my books for me to sign, and I know that I have reached her imagination, nourished her dreams. I sign her book, and touch the hand of that first primordial storyteller who sat beside a hearth fire long ago and said, “Once upon a time…”

Buy THE PEAR TREE at https://www.pennycandybooks.com/shop/pear-tree