Jan 15, 2023

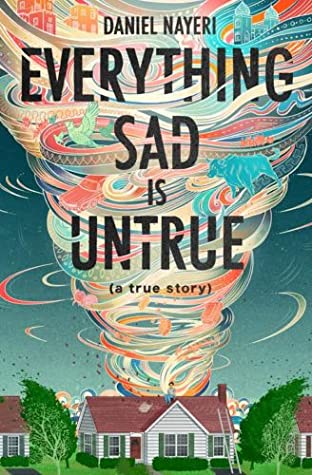

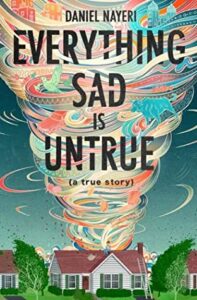

I read for escape, amusement, and information. But for me the greatest value of fiction is the entrance into other lives; the heart of fiction is empathy. Daniel Nayeri’s memoir-novel lets us escape our own world; it amuses and informs. But his chief task is to open the eyes and heart of the reader. “We can know and be known to each other, and then we’re not enemies anymore.”

I read for escape, amusement, and information. But for me the greatest value of fiction is the entrance into other lives; the heart of fiction is empathy. Daniel Nayeri’s memoir-novel lets us escape our own world; it amuses and informs. But his chief task is to open the eyes and heart of the reader. “We can know and be known to each other, and then we’re not enemies anymore.”

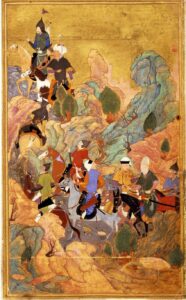

This book is full of riches: suspense, pathos, comedy. It takes me into lives and worlds I never knew: Persian myth and legend, middle-class family life, warm and sensuous, in modern Iran. A death decree when the mother openly converts to Christianity, a year in a surreal Catch 22 waiting for the UN Embassy in Dubai to grant refugee status, grudging support in an Italian refugee camp. And finally a 12-year-old refugee sitting by himself at the back of a class in bleak and hostile Edmond, Oklahoma, where the English teacher gives writing prompts and he tells his stories to sneering seventh-graders.

Persian legends: Destroying the Survivors of Kipchak Corps. source:artincontext.org/persian-art

middle school: image:daily herald

The narrator takes us back and forth and round and round, citing Scheherazade, who told a new tale every night to fend off execution. Though I’m accustomed to an old-fashioned, chronological account, with perhaps a few backwards glances, this is not difficult reading.

The narrator takes us back and forth and round and round, citing Scheherazade, who told a new tale every night to fend off execution. Though I’m accustomed to an old-fashioned, chronological account, with perhaps a few backwards glances, this is not difficult reading.

He tells us stories of many generations as well as his beloved nuclear family, especially his unstoppable mother. Gradually we learn how the 3-year-old watching his grandfather kill a bull in Iran became the 12-year-old in Edmond fleeing a brutal stepfather, but remained optimistic about the future.

His wide-eyed wonder at American ways makes us see them in a new light. There’s his hilarious comparison of American and Iranian bathroom hygiene, when he is finally invited to a friend’s house and tries to figure out how to clean himself. The class trip to a 98-year-old sod house, now a museum. The teacher tells him that in America we cherish historical things, and he thinks of his grandfather’s 600-year-old house ina walled garden lined with mosaic tiles, with a fountain and fruit trees.

sod house museum image:trip advisor

a courtyard garden image:pinterest

An outcast in a foreign land, he cherishes his memories. In an afterword, Nayeri explains that while he changed names, created a few composite characters, and adjusted the timeline, these memories are as truthful as he can make them. “A patchwork text is the shame of a refugee. I am afraid I did not have access to family records, historical documents, or even most of my family members. Perhaps I misunderstood a great deal, in the way that a child misunderstands, but those are the myths I believed at the time. This was my life, as I experienced it, and it is both fiction and nonfiction at the same time. Your memories are too, if you’ll admit it.”

Daniel Nayeri

Nayeri’s memories are moving, sometimes heartbreaking, often comical. I learned so much about ancient Persia and modern Iran and what it is to be a refugee. I fell in love with this twelve-year-old boy.

Aug 23, 2020

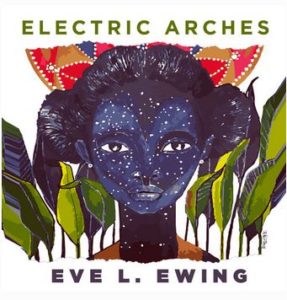

image: book cover: collage-style face of African American girl in blue with green leaves and multi -color disk.

(Photo of Eve Ewing by Lauren Miller: smiling African American woman at mike wearing yellow shirt with slogan: We All We Got.)

The purpose of this blog is to recommend books that may have escaped your notice. If you go to Eve L. Ewing’s website you’ll see that she has received many awards, and considerable media attention. Trevor Noah, Ta Nehisi Coates, Alicia Garza – all have interviewed her to discuss her second book, The Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on the Southside of Chicago. Still, even books that get a brief flurry of publicity can disappear from view, and I’d like poetry-lovers to find this one.

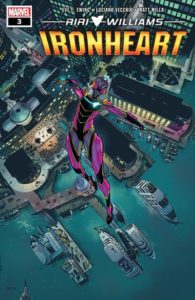

Ghosts in the Schoolyard led me to Electric Arches and to the author’s website. Ewing contains multitudes; she is a sociologist at the University of Chicago, community activist, visual artist, poet, and writer of Marvel’s Ironheart comics. Her website is a rabbit hole filled with wonders, where you’ll fall farther than Alice ever did, and discover posters, silkscreens, charcoal drawings, photographs, installations. https://eveewing.com/

image: comic book cover: Black woman superhero soars above city

Sometimes when I review a book of poetry I just want to transcribe the whole thing and have you read it. But this still wouldn’t give you all of Eve Ewing’s book, because it would leave out the varied typography, collage, mixed media. All I can do is write about some of the pieces that particularly spoke to me, and give you tempting tastes.

She introduces the book: When I was a little girl, I was allowed to ride my bicycle from one end of the block to the other, because that way my mother could come outside and stand on the sidewalk and see me…[A]s I rode my bike I would narrate, in my head, all my adventures. In my head I was shooting arrows, exploring dungeons, solving mysteries. In this way, my block became the backdrop of infinite possibilities, even if the reality of the cracked cement and the brick wall facing our window and the gangs seemed to constrain that possibility….

image: brick wall with graffiti and broken windows. from pixabay at pexels

Ewing’s jubilant imagination still creates light from dark matter. Hers is intimate poetry that presents a whole world, celebrates a rich life in a poor place, a beloved city-home of broken concrete and bricked- up windows. She goes straight to the heart of the matter, and her poetry to the heart of the reader.

As a child she would go to Chicago’s Navy Pier with her father, where he had a booth to draw portraits.

Back then there was the ferris wheel

and the 21st century McDonald’s

with the glass orb you can touch and pink lightning

comes to your fingerprints like a fruit punch stain

and not much else. You’d barely recognize it.

Navy Pier was a new and desperate thing,

and instead of fireworks a man set himself on fire

and jumped in the water every night at ten, I’m not even kidding…

While her father worked, she sold

…glow sticks to pass the time,

Making chains of them and hanging them on my skinny arms by the dozen,

Yelling at tourists the slogans I invented – light up the night with a glow light!…” t Work with My Father

image: cloudy sky, tall skyscrapers behind riverfront amusement park, ferris wheel and boats. pixabay at pexels.com

She writes about the demolition of a community hospital:

The first stone is the hardest

which is why they don’t use hands anymore

Too much, the push of the granite on the pads of the fingers….

Wrecking balls don’t get arthritis or cry

or show up on the site with lunches that their wives made,

bleary-eyed, standing in worn housecoats in the darkness.

The dynamite never says, ‘But my uncle died here, in this hospital…

while the tremor spreads

and the walls come down.”

Columbus Hospital

image: man stands looking at site of demolished building derelict buildings in background. free creative stuff at pexels.com

A prose poem includes Moses, Abraham and Eve, the tribulations of Black people, “a people forever in exodus,” her simultaneous faith in superstitions and the science of the universe, and finally the main subject, her grandmother, president of the choir at Shiloh Baptist Church.

Even when I was tiny I could hear that she was singing even when she was not singing – no woman could offer you a piece of toast or a glass of gingerale in such a lilting, untouchable soprano, or tell you that Grandpa was going to hit you with a comb if you didn’t settle down and have it sound so like a Wagnerian opera.

[Grandma] is wearing a grandma uniform…she has just returned from singing at church and so her hair and make-up are impeccable, and has also changed into a pearl-colored cotton housecoat with faint traces of a floral pattern, and a pair of slippers….This particular housecoat thrives on against all odds, and rather than clashing with the hair and makeup…they exist in a sort of détente. They have tolerated each other for this many years and they might as well keep on keeping on.”

What I Talk About When I Talk About Black Jesus

Reading her poetry with three other Black poets in a small town museum, she is cold and lonely.

The work of the poet is not unlike the work of being Black

Some days it is no work at all: only ease, cascading victory,

the plentitude of joy and questions and delights and curiosities.

Other days you wonder if exile would be too lonely,

and figure it can’t be worse than thinking you won’t make it home…”

Sestina with Matthew Henson’s Fur Suit

Inspired by a quotation from Assata Shakur,** Black revolutionaries do not drop from the moon. We are created by our conditions, she imagines moon people descending and changing the world.

…and they sang while

they smashed a bottle on the squad cars…to say ‘this

here is christened a new thing.’ And they drove them down my street

and your street and your street, the tires painted to look like vinyl 45s

and the children tied yarn and ribbons to the windshield wipers

and the moon people turned them on high so that as they drove, the colors

waved in the sunlight…

Arrival Day

image: police car foreground, street scene with skyscrapers behind. jiarong deng at pexels.com

In Sonia Nadia McDonald’s article in the online magazine The Undefeated, “How to Get More Black on Broadway,” she quotes David Mendizabal of The Movement Theatre Company: “What are stories that we’re not seeing? I mean the first thing that came to my mind was joy. Black joy, brown joy.” https://theundefeated.com/ Eve L. Ewing’s poetry brings us times of trouble and times of joy; she brings us a whole world, evoking understanding, recognition and laughter.

**Assata Shakur – writer, member of the Black Liberation Army, escaped from prison, now a fugitive in Cuba

Feb 11, 2020

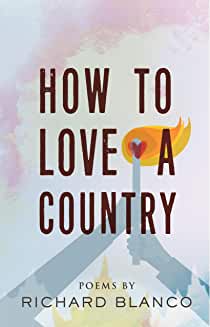

Review: How to Love a Country, Poems

by Richard Blanco.

Beacon Press, 2019.

I read a fair amount of poetry. I visit Poetry Daily almost daily. https://poems.com/ I don’t linger long over the many poems that remain obscure even after I puzzle over them, that seem to contain secrets known only to the poet. I just print the poems I like and save them in a three-ring notebook.

Though I took one poetry course in college, I remember very little about technical matters, such as the different forms and meters, so it may be presumptuous for me to review a book of poetry. But like music, poetry can speak straight to the heart. In a time when I, like many others, am frightened by the state of our world and our country, grieving at the evil done with our dollars and in our names, this book spoke to me.

Photo by Rosemary Ketchum from Pexels

Photo by Rosemary Ketchum from Pexels

Richard Blanco was the inaugural poet at Obama’s second inauguration. In his author’s note at the end of the book, he tells us, “…as the first latinx, immigrant, and gay man” in that role, he realized that his story “…is and has always been, a grand part of our country’s historical narrative.” Born in Madrid to Cuban immigrants, who moved to Miami when he was less than two months old, he is torn between the Cuban he imagines, and the American he is. “Destined to live with two first languages, two countries, two selves, and in the space between them all.” From these dualities comes compelling poetry.

Photo by Joe from Pexels

Photo by Joe from Pexels

He imagines how it was for his mother leaving Cuba, and wonders at her fierce love for her new country – “to love a country as if you’ve lost one.” When they visit DC she tells him, “You know, mijo, it isn’t where you’re born that counts, it’s where you choose to die – that’s your country.” He sang America the Beautiful in church with his mother – “…we sang our thanks to our savior for this country that saved us.” At the family’s first Fourth of July parade he sang for spacious skies “closer to those skies while perched on my father’s sun-beat shoulders.” He loves his country, “I still want to sing despite all the truth of our wars and our gunshots ringing louder than our school bells, our politicians smiling lies at the mic…”

Photo by Big Bear Vacations from Pexels

Photo by Big Bear Vacations from Pexels

In “What I Know of Country” he traces his love as he grew up. “When all I knew of country was a song and a book“ – the wonderful pictures of pilgrims in buckled boots, founders in wigs with quill pens, “When what I knew of country was only what I read from a map”- the vast land of mountains and rivers and cities he’d never seen,. When even though television brought images of war, “fantasy was still all I could believe of country.” As he grew older and learned the history of exploitation, brutality, injustice, “forgiveness became my country.” “I stayed, you stayed, we stayed for all the boys and girls returning as heroes, some without legs or arms…” for the Challenger disaster, the twin towers, the children in Sandy Hook, the people waiting for rescue in New Orleans after Katrina, “…feeling what we’ve always felt: to know a country takes all we know of love.”

Photo by hitesh choudhary from Pexels

Photo by hitesh choudhary from Pexels

His childhood in Miami was rich with Cuban culture, but he was always an outsider. From earliest days he was different. When he wanted to play with the girls, his family was ashamed and punished him, other boys picked on him. Almost grown, searching for a life, a place where he belonged, he moved to New Orleans, then Hartford, DC, New York. Finally putting down roots in Maine, he imagines the fterrible losses of exile.

“Dawn breaks my window and dares me to write a poem brave enough to imagine the last day I’ll ever see this amber light…” He imagines losing “the spring giggles of my brook,” “the scent of my peonies or pillows.” He imagines the heartbreak of the day of departure, experiencing everything for the last time. Holding his mother and promising to return though he knows he never will, visiting his father’s grave for the last time, saying goodbye to his husband who cannot go with him. “…a poem ending as I walk backwards away from his love at my door to open another…to harden into a statue of myself.”

After the November 2016 election he staggers through town doing errands, wondering about the chasm that separates him from people he thought he knew, people now wearing MAGA hats, his thoughts flipping through every fearful event on the planet.

photo with permission from istockphotos.com

photo with permission from istockphotos.com

In “Complaint of El Rio Grande,” he speaks as the ancient river. “I’ve breathed air you’ll never breathe, listened to songbirds before you could speak their names…before you created the gods that created you.” And then came countries, and civilization, and maps: “You named me big river, drew me, thick to divide…you split me in two, half of me us, the rest them. But I wasn’t meant to drown children, hear mother’s cries, never meant to be your geography: a line, a border, a murderer.”

Photo by Pixabay from Pexels

Photo by Pixabay from Pexels

He writes of the fantasies of the good old days in America, shallow and silly as a 50’s sitcom. He writes of the lynching of a black man in 1981, of a mother writing a poem for the son who died while she was in prison, the rich and poor living in different worlds in the same city.

Each poem is a heartbreak, a plea, filled with love and sorrow, with yearning and anger. After the Pulse massacre, with memories of all the joyful dancers shot down, he writes, “Let’s place each memory like a star, the light of their past reaching us now, and always, reminding us to keep writing until we never need to write a poem like this again.” After the massacre at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas high school: “Seventeen dead carried down hallways they walked, past cases of trophies they won…”

photo from pixabay at pexels.com

photo from pixabay at pexels.com

In “Declaration of Interdependence,“ a love poem to all of us, he tells us, “We’re the cure for hatred caused by despair.” He lists ‘we the people’: the farmer whose back has given out, the miner who can no longer make a living, the black boy killed by a cop, and the cop who killed the black boy. “We’re the good morning of the bus driver who remembers our name, …every door held open with a smile, …we’re the promise of one people.” He includes the Peace Corps alumni who collect African art, who reminisce about demonstrations and burning their draft cards and who now know “it’s time to do more than read the New York Times, buy fair trade coffee and organic corn.”

Blanco’s stories, his people, his courage in opening his heart, move me. I don’t know that they will move me past despair into action; I am worn out, just doing what I can in one small corner of injustice. But like the music of our great revolutionary movements – labor, civil rights, anti-war, women’s movement – his poetry can inspire and support those who are fighting to free us all from this particular troubled time.

Oct 18, 2019

Malaya, Essays on Freedom. By Cinelle Barnes. Forthcoming October 28, 2019 from Little A.

In her first book, Monsoon Mansions, Cinelle Barnes wrote of her childhood in Manila, and how her family and her life fell apart after her father left and her mother remarried. Her second book, of essays on freedom, takes us into a world that is all around us, the world and life of undocumented immigrants. “No citizen, left wing or right wing, really knows the nothingness, the nonbeing, undocumented young adults constantly live with and anticipate.”

Barnes came to the United States as a young teenager to live with and be adopted by her widowed aunt. After adoption, she would become a citizen. She was an A student at her arts high school, a star player on the soccer team. But there was a glitch in the legal proceedings: her adoption was not finalized until shortly after she turned seventeen. That delay changed everything for her; her entitlement to US residency and citizenship disappeared after age sixteen. Suddenly Barnes was an undocumented immigrant, and fell into that underworld of people who survive by any means necessary.

Barnes had many family members in the US, and she left her aunt’s home to move in with her sister, to a two-bedroom apartment that was home to thirteen new immigrants. The sudden switch was too much for Barnes. “[M]y spirit or gumption or essence departed from my body.” She became virtually paralyzed, hiding in her bed, unable to function.

image: Craig Adderley pexels.com

“My sister, who was already like a mother to me, intuitively acted as my physical therapist. Ever wary of talking about mental health, as most Filipinos her age were and still are, she committed herself to my functional recuperation.”

Her sister insisted that Barnes join her in her work. “She forced me to move my body. She said that I should clean houses with her and our brother, convinced that if I could hold a brush and get into the rhythm of scrubbing in an up-down-up-down motion, I could get better. I scrubbed grout on my first day.” She moved on to washing windows with a circular motion, then vacuuming, moving rhythmically, making patterns in the carpet.

image: rawpixel.com pexels.com

We know that exercise heals our spirits as it strengthens our bodies. The hard labor and repetitive movements had neurological as well as more general physical effects. With her strength and renewed energy, she and her siblings took on more jobs, and their small business prospered.

Barnes remained undocumented, finishing high school, graduating from college at 23, all the while working long hours to support herself, as a house cleaner, a nanny, a laundry attendant, a supervisor in a coffee shop staffed mostly by undocumented workers. She and a friend started a sewing business, designing and making custom wedding accessories and selling them on the internet, but the business became so successful they could not keep up with it, and as undocumented workers they had no access to financing to expand the operation.

image:banksexpectbestfrompexels_

Marriage to her long-time boyfriend, an American citizen, put her back on the path to naturalization. Even the happiness of the wedding with friends in Central Park was clouded by the marriage license clerk who had interrogated her, suspecting the marriage was a fraudulent green card scheme.

image: pixabay pexels

Barnes vividly pictures her experiences. As a nanny, she was a confidante to the children’s mothers, who told her all about their lives while knowing little of hers. She enjoyed the unbalanced friendships, where she was welcomed into privileged worlds of museums and theater. At the same time, she felt kinship with the other Filipina domestic workers she encountered. “I wanted them to hold on to the idea that a young Filipina could maybe, maybe, one day write about the Filipino immigrant experience—that maybe, maybe, one day, someone would write about them and acknowledge their sacrifices.”

image:nationaldomesticworkersalliance.jpg

In the laundromat she was under time pressure to wash many loads of sometimes disgustingly soiled clothing while restricted to the few machines not reserved for the self-serve customers.

image:adrienneandersen pexels.com

She found something like a home in a Greenwich Village café, where most of the young workers were undocumented, from all over the world, and the sympathetic owner quickly put her in a management position when he recognized her skills. But they were all traumatized when the immigration authorities raided the café and arrested one of the cooks.

As a teacher and writer, Barnes has studied trauma and the mental health of immigrants. She brings us thoughtful understanding of the psychological effects of her experiences. Malaya is a vivid, insightful picture of life in the shadows of our immigration system, as well as a portrait of an exceptional woman who overcame many obstacles to achieve the life she wanted. It is particularly compelling reading now, as chaos and cruelty rule our borders.

May 2, 2019

Book review: Laura Hershey: on the Life and Work of an American Master, edited by Meg Day and Niki Herd. Pleiades Press, 2019

(cover image not yet available, this is the photo on the cover)

(cover image not yet available, this is the photo on the cover)

.

Three presses (Pleiades Press, Gulf Coast, Copper Nickel) have collaborated to produce the Unsung Masters Series of books about the life and work of unjustly forgotten authors, presenting their writing, and biographical and critical essays about their lives. Laura Hershey was a poet and fierce disability rights activist who died in 2010 at 48. I had never heard of her. One of her themes in these selected poems is the invisibility of disabled people, how others choose not to see them, not to know of their lives.

We define some disabilities as “normal.” I’ve been wearing eyeglasses since I was ten, but nobody considers me “disabled” or different. In part disability resides in the individual; in part it is created or defined by society and custom. Why was my 1960’s house built in such a way that my friend in a power chair cannot reach the bathroom? Why are there raised curbs and thresholds everywhere? Why don’t movies all have closed captioning, and live theaters show dialog on a screen?

Yummy! (but inaccessible). image by lisa fotio from pexels.com

Yummy! (but inaccessible). image by lisa fotio from pexels.com

Those of us who are not now disabled are likely to age into various degrees of disability. Despite the losses – loved ones gone, activities I can no longer do – I love getting old because my thoughts are much more interesting than before. But I don’t like the pain: I’m always hurting somewhere. In his 90’s, with relatively minor disabilities, my father told me that when he was in his 70’s he thought he wouldn’t want to live like that, but he found that he still looked forward to each day.

I have read a few books* focused in part on disability. They make me think about things I never considered, see the world through a different lens. I hope I understand the limits of my own understanding.

Laura Hershey was physically disabled – she retained vision, hearing, speech, sensuality, and intellectual ability, but was unable to move most of her body. She needed a personal assistant to position herself, to feed, bathe, and dress her. She wrote on a computer, using voice recognition.

She wrote poetically or plainly, or even in doggerel. The subjects vary: poetry, sex, Robin Stephens, her lover for over twenty years, her own body. Most of the poems selected in this book are about disability, addressing two audiences – activists, and ableists. But the collection also includes a few lyrical love poems from a long relationship. Her disability poetry outrages me, and it makes me laugh and cheer.

Hershey and Stephens devoted their lives to fighting for the rights of disabled people, especially the right to live outside institutions and receive the services that would make that possible. Before a demonstration against institutionalization she wrote nine stanzas of simple doggerel.

Special Vans

The city’s renting special vans

the daily paper reads

The cops are getting ready

For special people with special needs

…

They put up special barricades

To try to keep us out

Still we’re in their face

Still we chant and shout

What’s so special really

about needing your own home?

If I need pride and dignity

is that special, just my own?

Are these really special needs

unique to only me?

Or is it just the common wish,

to be alive and free?

An arresting picture – Washington DC 2017. Image: adapt.org

An arresting picture – Washington DC 2017. Image: adapt.org

Hershey confronted the notion of independence, a concept so glorified in our country that many refuse to see that we are all interdependent. They ignore the assistance that we all need, but only some receive – from families, community, government. In an interview she said, “I do need a lot of help. But I consider myself independent…That doesn’t mean I’m totally self-sufficient. That means I have control over the choices I make, what I do with my life.”

In the poem In the Way she recognizes how people in wheelchairs can use their disability as a weapon in the fight. It’s thrilling, as though we are watching the birth of a movement. She had been apologetic when her bulky chair took up too much space, got in the way. And then she realized

If I alone can be so much

and so often in the way

if I can create such worry among waitpersons

such consternation in concert halls

such alarm in the aisles of grocery stores

just imagine the aggravation a dozen

or two dozen

or three hundred

people using wheelchairs can cause people

who would rather not see our needs

or hear our demands

or acknowledge our rights!

Just imagine!

image: Action for Access

image: Action for Access

She and Stephens are both in wheelchairs and both leaders in the fight. In A Day, Hershey wishes for a day together free of the struggle, and dreams of a victorious future.

A day, Robin,

Just one single day out of the future

we hope we are building

…

A morning waking slowly – taking our time

to get into our chairs and get the motors going

– not urgently,

with no demonstrations to prepare for,

because justice demonstrates itself these days;

no meetings,

which have mostly been replaced

by simple understanding;

not even a conference to attend,

because issues like caregiver abuse

and work disincentives

were settled long ago.

I’d give us

a quiet afternoon among trees, Robin,

…

Or we’d take poles to a mountain river.

Fish surface as rain begins to fall. Huddled together

in the rain, we draw out enough rainbow

to satisfy two

stomachs and two clear minds.

image by emre can from pexels

image by emre can from pexels

Is there a ‘me’ apart from my body? Age, illness and disability may cause us to think more about that puzzle. In Monster Body Hershey plays with language to figure it out.

My back’s shell-sharp curve, my thin wrist bone,

limbs that do not twitch beyond the digits;

right lung so different from left – the leader, thrust

forward, fuller-breathed,

pushing against ribs; while its more delicate mate

shrinks,adjusts inside a smaller collapsing cage…

Monster mine, monster body,

one I would not trade.

Not for gold, not for leading roles,

not for promise of perfection, the protection it affords.

…

but the pronoun ‘my’ distorts the relationship; the

spaces

imply a separation that does not exist.

‘Have’ stands too distant.

MonsterBodyMine, instead –

this makes am true….

MonsterBodyMine.

With my body, in my body, as my body,

by my body I journey.

It is my medium for learning, for love.

It is my lens, my light.

MonsterBodyMine

I myself have been only an intermittent activist, a little writing, a little marching, a lot of teaching and preaching, mostly to the choir. I’m proud of what I’ve done, but most of it has been working to boost one person up over the wall rather than tear down the walls, to make systems a little fairer, rather than attacking their rotten roots.

I’ve learned that calling disabled people courageous, inspirational, is as offensive as unwanted pity. But I am always moved by the courage of those who fight for civil rights. They fight against the odds, persistently, for an imagined future which is long in coming if it comes at all. They are the outsiders, the unseen, and they pound relentlessly on the doors of power. These are my heroes, and I call them courageous.

image: nat endowment for the arts from pexels.com

image: nat endowment for the arts from pexels.com

*BOOKS I RECOMMEND (links are to my reviews)

Good Kings, Bad Kings, by Susan Nussbaum (novel) click

Too Late to Die Young, by Harriet Johnson (memoir)

A Certain Loneliness, by Sandra Gail Lambert (memoir)click

Thinking in Pictures, by Temple Grandin (memoir)

Mar 3, 2019

Book Review: They Could Live with Themselves by Jodi Paloni. 2016. Press 53. Winston-Salem, NC.

These eleven short stories give us a year in the life of Stark Run, a fictional Vermont town. Common themes and recurring characters link the stories together, as the lives of the characters are linked in the intimacy of this very small town.

Sometimes the intimacy is a comfort; sometimes it is stifling. Indeed, in the first story we meet Molly, who wants to run away from her finally almost-empty nest, who wonders “is it too late to exchange one kind of life for something altogether new?” In the last story, Molly’s son Sky, a year out of high school, wrenches himself out of the life he loves in Stark Run and runs away to pursue his art in Philadelphia, first wandering through the village before dawn, taking pictures.

image by simon robben from pexels.com

image by simon robben from pexels.com

Wren, the owner of the general store, is “surprised at the kind of drama that play[s] itself out in this quiet town.” This book has no explosions, brutal fights, murderous villains, no bleak dystopia resisted by sexy heroes. Instead, Paloni makes us care deeply about her characters because they seem real in their virtues, flaws, and yearnings. She knows them so well she might almost be Wren. “Over the years she’d served up hot coffee and listened to a host of woes.”

image pixabay.com

image pixabay.com

Paloni creates suspense, sometimes with sexual tension, sometimes with a situation more heart-breaking or ominous. What kind of trouble will the three high school girls cause for Jack? Will Charlotte’s mother come home from rehab for her twelfth birthday? Charlotte is sure she will; we’re sure she won’t. Who is the stranger who pounds on the door of Wren’s store late at night, insisting she let him in?

The characters are ordinary heroes. Meredith, who makes assemblages in wire and clay, came home two years ago to nurse her dying mother, and persists in her art though she now teaches full-time at the high school. After almost fifty years as a brilliant English teacher, Maeve stands up to the ignorant, treacherous principal she despises, to make her own decision about her future. Wren drives hours through a blizzard to help a man and his dying wife, both strangers.

image: lisa fotios from pexels

image: lisa fotios from pexels

Paloni treats the big themes: death and loss, family love, sex, identity. Meredith mourns for her mother as the anniversary of her death approaches. One story begins with a girl witnessing her little brother’s drowning. The accident is related so abruptly and casually that it hardly feels like a death, and the story is really about the girl longing for her mother, who is lost in grief. Molly’s husband Jack is bereft when she goes away for a ten-week retreat; “[s]he was as gone as a person can get outside of death, as far as he was concerned.” Claudia misses her divorced father, who no longer visits.

In such a small town, adults and youth are not isolated from each other. It takes a village, and the adults look out for the kids as best they can. Sometimes they judge them harshly, sometimes they are tolerant, recalling their own youth. The young are rapt with sexual desire, whether it’s 14-year-old Rory yearning after an older girl, or Sky engrossed in his girlfriend Emily, loving every inch of her, yet tearing himself away to become his most important self.

We see marriages from both sides. While Molly is exhausted by years of marriage and raising five children, and eventually goes on a long retreat, Jack doesn’t know what to do without her. He’d retired and thought they’d spend more time together, and now she’s left. “…Molly had said that her journey had nothing to do with him, which was supposed to make him feel better. It made him feel worse. When did she start saying things like her journey? And how could her journey have nothing to do with him? They were in this life together.”

Addison’s wife Ruby leaves him suddenly after twenty years of trying to change him. She returns roaring in on a motorcycle, dressed in leathers, hoping to resume their life together. But he has become comfortable with himself, has even begun to find a more suitable partner, and realizes that the central question is “Who is it that you want to be?”

image: leo cardelli from pexels

image: leo cardelli from pexels

We see the characters working out the answer to that central question; the title of the collection is apt. Some can live with themselves in the town which formed them, and some have to leave to follow the dream they first dreamed there. Leaving is hard, because their ties to Stark Run are strong. Staying is not always easy either, as they must find their true selves in a place which has already created a space for them, a space with a particular shape which may no longer fit.

These stories are beautifully-written. Paloni’s writing is clear and lyrical, and her observations, whether of scenes, experiences, or feelings, are entirely accurate. I love good writing, and can’t read far in a book when the writing is clumsy or clichéd. But more than her style, I admire Paloni’s gift of creating engaging characters, each a fully-realized individual. She has given us a whole living town in deeply satisfying stories.

BUY THE BOOK

I read for escape, amusement, and information. But for me the greatest value of fiction is the entrance into other lives; the heart of fiction is empathy. Daniel Nayeri’s memoir-novel lets us escape our own world; it amuses and informs. But his chief task is to open the eyes and heart of the reader. “We can know and be known to each other, and then we’re not enemies anymore.”

I read for escape, amusement, and information. But for me the greatest value of fiction is the entrance into other lives; the heart of fiction is empathy. Daniel Nayeri’s memoir-novel lets us escape our own world; it amuses and informs. But his chief task is to open the eyes and heart of the reader. “We can know and be known to each other, and then we’re not enemies anymore.”

The narrator takes us back and forth and round and round, citing Scheherazade, who told a new tale every night to fend off execution. Though I’m accustomed to an old-fashioned, chronological account, with perhaps a few backwards glances, this is not difficult reading.

The narrator takes us back and forth and round and round, citing Scheherazade, who told a new tale every night to fend off execution. Though I’m accustomed to an old-fashioned, chronological account, with perhaps a few backwards glances, this is not difficult reading.